by Elisabeth Hegmann

Betray not thy divine gifts to men until commanded by the Muse who bestowed them upon thee and of whom thou hast become worthy. For the artist, the beautiful mortal, the god transforms himself into imagination. – Eusebius

The first overture was not effective; stop! thought he, the second shall rob you of all thought – and so he set himself to work anew and allowed the thrilling drama to pass before him, again singing the joys and sorrows of his heroine. This second overture is demonic in its boldness . . . – Florestan

1

Flora was more or less what Dobbs expected from the moment she slid down the mahogany banister. The girl – or was she a young woman? – came to a stop barely an inch in front of him. She was panting a little, and flushed. He pushed his glasses up the bridge of his nose and took a step back.

“You’re Dobbs,” she said in a strong voice. “The music room is this way, come on.”

She started through the hall and Dobbs tried a quick walk, then broke into a trot to keep up with her. They passed into a narrow passage with a number of paintings. One of them was of the composer Robert Schumann; and his wife Clara, the pianist, was nearby. Another was a rendering of the ancient Greek myth of the Sirens, the daughters of the storm god. A conservatory to the left housed large tanks filled with seawater from the nearby cove, and a variety of plants grew above and below the surface. Though the glass doors were closed, a brackish smell filled the corridor.

He followed Flora into the next room on the right. She flopped down on a settee and stared at him without embarrassment. The late summer sun glared off of a French horn. Dobbs stepped to the side to get the light out of his eyes. As he did so, he spotted the young man sitting backwards on the piano bench, facing him and tapping his foot nervously on the intricate parquetry, a violin clutched in his hand. This would be Eusebius, Flora’s twin, who Dobbs knew was called Zeb. Zeb nodded slightly, held up a hand in greeting, and walked to the far wall to rifle around for a piece of music in the filing drawers that stretched from wall to wall, and ceiling to floor. It occurred to Dobbs that the sheet music they owned surpassed the collection at his university.

Zeb found whatever he was looking for, set it on a music stand, and returned to the piano bench to stare at his feet.

“He’ll talk eventually,” Flora said. “He’s just shy. I can tell he likes you, though.” There was a hint of mischief in her voice and she burst out with a hearty, infectious laugh that Dobbs liked. Zeb made a face at her, but then smiled.

“Anyway,” said Flora, “he wants you to look at the music.”

Dobbs stepped over to the stand and as he glanced at the music he felt a thrill. On the stand he saw what was perhaps his favorite Schumann piece – an obscure song no one performed anymore. Astonished, he looked at Zeb.

Zeb smiled. “My best parlor trick,” he said in a soft voice, almost a whisper. “But it’s a curious choice. I have to admit there are others I prefer.” Despite his quiet tone, he spoke with a kind of firm resolve, and unlike Flora, his pale skin showed no flushed patches.

Dobbs took a breath to respond, but from the hall he heard a woman’s high-heeled shoes on the marble floor. Zeb and Flora exchanged a look. “Here she comes,” said Flora furrowing her brow.

Dobbs didn’t like her tone. He had heard of Dr. Linnell of course, a household name to every family who had ordered a Human By Design child within the last few decades. Growing up he had heard his mother criticizing Linnell to his father, saying she had abandoned Human By Design after she had helped found it. Dobbs later learned that Linnell had been asked to resign. It made no difference since Human by Design had had to end its operations only a few months later due to increased opposition from the public. In any case, Linnell had retired and become a virtual recluse in this mansion on the Mediterranean coast. As her footsteps came closer in the hall outside, it struck Dobbs how strange it was they were together in the same house.

He tried to smile and think of the appropriate things to say, but already there she was in the doorway. Her tall, bulky frame filled it and her dark hair blotted out the sun from the conservatory across the hall. She rolled her eyes as if in permanent disgust with the world, but then when Dobbs least expected it she glared at him shrewdly. He tried to guess her age, but her face was so pitted with old acne scars that it made the task difficult. Dobbs admired that she didn’t try to cover the damage with make-up.

“Flora!” Linnell said, though still looking at Dobbs.

Flora pretended to have great interest in a clarinet. “I’m busy, Mum. I’m looking at some music, and this clarinet needs-”

“Come and sit up here,” said Linnell.

Flora stomped across the floor and sat so close to Dobbs their legs were touching.

“And Zeb, of course it’s okay for you to be a bit shy if you must, but why don’t you at least move closer.”

Zeb dragged the piano bench across the floor with a prolonged screech.

Linnell’s eyes still had not shifted away from Dobbs. She nodded slowly, and Dobbs watched her large bun of dark hair move up and down. “Yes, she will like him just fine,” she muttered to herself, as though Dobbs couldn’t hear her.

He wondered who she was. Did she mean Flora? He felt disconcerted and nervous.

Linnell sat down on an amp across from him and her voice became sing-songy. “I wanted us to be like the Bach family, Mr. Dobbs. A large number of musical children, but I managed only these two. I decided to start with Schumann’s precious demons, Florestan and Eusebius, but I never had another success or got to be Bach.” She sounded sad and weary. “As an ‘up and coming’ musicologist, you will find our family of great interest.” She pronounced the words ‘up and coming’ with distaste, and made ‘musicologist’ sound like an unfortunate disease with no cure. Clearly she favored performers, and had the same disdain for musicology he had encountered in the university where he had just finished his degree.

When Dobbs had spoken to Linnell on the phone about this commission to write a book on Flora and Zeb, he had hadn’t mentioned his own past as a Human By Design failure, which nobody needed to know, or that musicology was not his calling but his compromise since it had been too late to become an accomplished musician and make it to the renowned musical utopia, Musette.

“I want the book written from a musical perspective, which is why I have hired you,” Linnell continued. “And I would also like to stress that this is an historical opportunity.” She looked at Dobbs seriously over her glasses. To avoid her gaze, he took off his own glasses and pretended to polish them. “Zeb, why don’t you play something for Mr. Dobbs?” she said.

Zeb sighed and picked up his violin.

As he tuned, Flora leaned over to Dobbs. “This is Mum’s dramatic way of showing you we’re prodigies,” she whispered.

“How old are the two of you, anyway?”

“Nineteen.”

That surprised him. Apparently living in this isolated environment had made them naïve and childlike – they looked/seemed no older than fifteen.

Zeb was now ready to play and he looked at Dobbs with a stern hopefulness that Dobbs found endearing, but Linnell only looked away and smoothed out her severe gray skirt suit. Then he placed his bow on the strings and at once all thoughts were driven from Dobbs’s mind.

While Zeb played, it was as though all of Dobbs’s most yearned-for dreams were revealed to him for the first time, and it was possible for him to have any of them if he could only reach far enough. When Zeb finished and Flora took over at the piano, Dobbs was filled with an almost overwhelming sense of invigoration as though all his childhood wonder had been restored, lying just beyond an unknown horizon. But when they had finished, the reality of his prison of a career in musicology descended upon him, bearing him back down to reality. He tried to replay in his mind the essence of the music he had just heard, but was only able to conjure up a dim and ghostly recollection. He couldn’t decide whether Flora and Zeb had played known pieces, or if the music had been composed in the moment, pulled out of some previously untouched musical dimension.

Linnell smiled gravely at Dobbs. She leaned closer to him. “Imagine them both playing at the same time,” she said, glancing at them with something like affection.

“Very talented,” agreed Dobbs, unable to find any other words. His voice was hoarse and his throat dry.

“But we will save that for another day, won’t we?” Linnell stood up and strode out of the room, the sound of her heels punctuating his racing thoughts. “Be here with your bags in the morning, Mr. Dobbs,” she called back from the hall.

2

“We’re not actually supposed to be in here except when we’re practicing,” said Zeb. “But Mum won’t know. She’ll be in the conservatory for hours yet.” Zeb was giving Dobbs a tour, and they were standing in an auditorium that Linnell had built onto the house. Dobbs was not surprised that the auditorium was off-limits. That morning he had already learned he was not allowed entrance to the conservatory – not even allowed to knock – and the door was always locked.

“There are many rules in my house,” Linnell had told Dobbs when he had arrived with his bags. “Strictness has been necessary. I have had to be both mother and father to my children.”

No kidding, Dobbs thought. In the past, human designers had built parents’ children to their specifications according to a comprehensive checklist – boy or girl, level of intelligence, physical characteristics – and then later handed the babes over to parents who were hoping for world-class intellectuals or athletes. All of it was playing God, to be sure, but Linnell’s brand of totalitarian control was even more frightening to him. She had not only designed and made Flora and Zeb, but expected to control their lives.

Dobbs had never heard of such a specific application of human design, either. Linnell had not just attempted to create a musical phenomenon; she had tried to replicate the genius of the two sides Schumann had exhibited in his life and music – the exuberant Florestan and the reflective Eusebius. Even when used as pen names, his two sides had been very different in both their personalities and their analyses of music. It was a radical notion to try to recreate Florestan and Eusebius, and Dobbs was still unsure how to approach writing a book about it.

Zeb led him to the opposite side of the hall. “Mum had this window put in,” he said. “It’s a pretty unusual thing to have in an auditorium, of course, but she likes the view of the sea.”

The window revealed a panoramic view of the coastline. The house sat on a low bluff, the auditorium closest to the precipice. Dobbs looked out the window at the blue water below. There were rocks along the edge, but in the middle the inlet was clear and deep.

“You like the water,” said Zeb. He missed very little.

“I was designed for the water,” said Dobbs. “A diver, actually. And you can’t help liking an element you’re talented in, at least a little. But I can’t dive anymore. I was injured before I could become really competitive.”

“That’s when you went into musicology?”

“Right. It was too late to pick up an instrument. My back would prevent me from putting in the practice hours anyway.” Standing at the window, he told Zeb the story about how they had put him in the water as an infant so that he didn’t ever recall life away from it. He told him music was what he really loved, that his injury had allowed him to make a break for it, but his lifelong dream of becoming a musician was out of the question. Musicology was as close as he could get.

Dobbs’s parents had blamed him for his injury. They said it was because he never had his full concentration on diving. He wondered now if they were right, if in the split second when, at age twenty, he was preparing to dive in a major national competition and made his small error in judgment (small, but at that height enough to break his back) if he had really been ready. Instead of focusing, maybe he had been thinking about Beethoven’s Emperor Concerto, which had obsessed him at the time. Whatever he had been thinking, a second later his back and then his head hit something hard, and he plunged into darkness. Days later he woke and stared at the blank hospital ceiling, the Emperor still running through his head. When the doctors came in to speak to him, his first coherent understanding was that though he would walk again, what he had been could not be regained. In his pain, he felt the first small hope of moving towards music. And for a short time, he even yearned wistfully, though unrealistically, to make it to utopian Musette.

He had always studied music theory, had always written about music. He had always had words, even if he didn’t have music itself as a language, and in those months in the hospital he wrote pages and pages. When he had finally been discharged and his parents’ disappointment was fully realized, he enrolled in a music school halfway across the country, his goal to find a place where his family couldn’t reach him. They had made him from the beginning, adjusting and tinkering and hammering; now he just wanted to be left to himself.

“We have an indoor pool here. You can swim if you want,” said Flora. She was standing behind him holding a flute. He hadn’t seen her come in. Zeb shook his head at her in disgust,

apparently appalled at her insensitivity.

“It’s okay,” said Dobbs, “I still swim to relax. I just don’t dive anymore.”

“Did you ever swim in the ocean?” said Flora.

It was strange, but the truth was that he hadn’t. He had only swum in pools – engineered bodies of water, like his own body. His parents had always told him that lakes and oceans were dirty and he could get infected.

“No, never,” he said. His voice was sad, and Flora leaned her head against his shoulder. He smiled. It was a sweet gesture – a child’s gesture.

“Show us how to swim in our pool,” said Zeb, “We only know how to splash around. Mum would never let us learn.”

“I’d be glad to show you,” said Dobbs. He suddenly felt angry with Linnell, sure that she was controlling Flora and Zeb by keeping them ignorant; for one thing, she had clearly never told them about Musette. So many yearning supplicants had been turned away from the place over the centuries, but Flora and Zeb, with their great talent, would undoubtedly be accepted if they desired.

3

From his upstairs bedroom window, Dobbs could see the sprawling wing of the house that contained the conservatory, its tanks impenetrable gray-green cubes in the summer dusk, the water dense with plants. In the three weeks he had spent in the house he had never had the urge to see it more closely, though Linnell seemed to spend all her time there. Zeb was trying to tell him about the lab farther down the hall.

“Mum grew us in little dishes in that room,” he was saying. “There were failures, too. She killed them, of course.”

Flora and Zeb, spread-eagled on Dobbs’s giant bed, had worked their way almost to the bottom of a bottle of wine Dobbs had been hiding in his drawer. Dobbs listened to Flora and Zeb practice for six hours every day in either the music room or the concert hall. They had just completed their session; Linnell had said she would be in the conservatory all evening. Dobbs wondered how she kept from choking on the strong briny smell.

“She killed her own children,” he muttered in wonder, sitting on the bed and pushing aside a letter he had received earlier – a troubling letter. He had to decide whether or not to share its content with Flora and Zeb.

“They weren’t children to her, silly,” said Flora in matter-of-fact, if slurred, tones. “They were just successes or failures.”

“Yes, that’s exactly it,” said Dobbs. His own family had practically killed him driving him to be a success, and then they had considered him as good as dead once he was a failure. You couldn’t win. “But what kind of ‘failures’ do you mean?” he continued, lighting a cigarette. He had started smoking a few days after he left the hospital. His soul was ruined; he might as well ruin his body as well.

“Give me a cigarette and I’ll tell you,” said Flora. She pulled the vase they’d been using as an ashtray closer. Linnell had forbidden Dobbs to smoke in the house; it would damage the children’s tender vocal cords. Dobbs handed Flora a lighted cigarette and offered one to Zeb, who shook his head.

“Well, actually I don’t know anything about it, but at least I got a cigarette,” said Flora. Dobbs slapped her playfully and she protested. “Mum won’t talk about it,” she laughed, “but I do know there were plenty that just didn’t live up to her hopes. I know there was at least one she put a lot of work into that ended up, um…not as successful as Zeb and me.”

Dobbs considered. “Are you ever afraid she’ll find some little fault with you, that you’ll fail to meet her expectations, and she’ll decide to wipe you out and start over?”

Flora’s eyes became wide and she took a bigger drag on her cigarette, but Zeb shrugged. “I think if she saw one or both of us as a failure, it would probably kill her,” he said.

“How can you become successes or failures if you’re kept locked away in this house? Does she expect to keep you here forever?”

“We’ll have our debut concert in the auditorium at the end of summer,” said Zeb. “I think she wants you to write about it as the grand finale of the book.”

“What do you think will happen after the concert ?” Dobbs asked.

“If we play well, we can get away from Mum,” said Flora, her face flushed and her voice excited. “We can tour for the rest of our lives and see the whole world.”

“I’d rather go someplace quiet,” said Zeb. There was a touch of irony in his voice, the knowledge of how different he and Flora were.

“Don’t you want to be famous?” said Dobbs.

“Not really,” said Zeb. Flora looked away.

Dobbs thought he understood. He had wanted to be famous once. He wasn’t sure what he wanted anymore. Since excellence had rejected him, and he had rejected both mediocrity and failure, where did that leave him? Nowhere, clearly.

“Who’s your letter from? What does it say?” asked Zeb. He squinted at the crumpled piece of paper on the bed, trying to decipher its shorthand. Dobbs folded it up and set it aside, considering whether he should set himself against Linnell by enlightening Flora and Zeb about Musette. Knowing what it was to be controlled by one’s mother, he supposed it was his duty to do so, even if it meant losing the commission to write the book.

The letter was from his college roommate, Percy Stevens, who had always been fascinated with Musette. Dobbs handed them the letter, but they complained they couldn’t decipher Percy’s handwriting, so he read it to them. Percy told of a massive expedition that was to take place around the end of the year – tens of thousands of people would go to Musette and try to get in. But when Flora and Zeb pressed Dobbs for more information, his determination to tell them the whole truth failed him, and he said only that the place had tens of thousands of citizens and had been inhabited since the 17th century. He didn’t mention music.

“We’ll go to Musette on our tour!” said Flora.

Suddenly they heard loud footfalls on the stairs. They tamped out their cigarettes, Flora pushed the makeshift ashtray under the bed, and Zeb disposed of the empty bottle. But it was the letter that worried Dobbs, and just as the door opened, he slipped it under a pillow and opened his notebooks to make it look as if he had been working on the book.

“I have warned you about smoke,” said Linnell. “I could smell it all the way down in the conservatory.” She glared at Dobbs’s notebooks, then turned her focus to his rumpled shirt.

“You should replace those shabby starving artist clothes with a respectable wardrobe,” she said. She dug around in a pocketbook and stuffed something in Dobbs’s hand. After she had marched out the door, Dobbs looked down. In his hand was a wad of hundred dollar bills. A small piece of the fortune made through Human by Design.

“Just ignore her,” stressed Zeb.

“Please stay with us, Dobbs,” said Flora. “And bring us more things from the outside. Mum won’t let us have things.”

Dobbs sighed. “Your mum wants me to write a biography of the two of you. But I don’t know how I’m supposed to do that when you haven’t had any exposure to the world. You haven’t had lives yet.”

“Then take us to Musette with you,” Flora said quickly. “We can all live there.”

Dobbs laughed with more vitriol than he intended, and Flora looked away, hurt.

“I’m not laughing at you, Flora. It’s just that it’s not that easy to get into Musette – for some of us, anyway.”

None of them spoke for a while.

“What’s it like listening to us play?” asked Zeb. “Mum never really tells us.”

“In a way, it’s like listening to Schumann, only more intense,” Dobbs said. “You reach for something that you want more badly than anything, something without a name, and then you have a feeling of soaring into a sublime and impossible place, where you see a veil. You sense that what you want is just behind it, and one day you hope to tear it aside and be united with whatever is beyond.” He smiled at Zeb. “That’s one of the things I’ve been writing in my notebooks.”

Flora tried to ask more questions about Musette, but Dobbs waved her away and pretended to work on the book. He knew Musette would instantly take Flora and Zeb, and he was jealous. Jealous that they would make it and he wouldn’t, jealous also that they would be shut off from him; because there was more to it for him, even beyond the intoxicating power of their music, another truth he had been attempting to hide. He had anticipated his attraction to Zeb from the first time he had seen him. But the fact that he was also attracted to Flora surprised him. The absurdity of the situation made him smile. His fluid sexuality was something else his parents hadn’t ordered on the checklist.

He couldn’t let Linnell see that he had gotten too close to Flora and Zeb. But neither could he let them get too close to Musette. That place would take them away from him as certainly as Linnell would, if he ever told them about it.

4

Dobbs had never really studied the portraits of Clara Schumann he had seen in his textbooks, but as he paced the hall it was difficult to pass by her without admiring the graceful curve of her neck, the knowing look in her eyes. He had forgotten her physical appearance, but her heart – and Robert and Clara’s tempestuous and passionate love story – had made an indelible impression on him.

Robert, nine years older than the pianistically gifted Clara, had known her from the time she was a small child – in fact, was inspired to take lessons from her father, Friedrich Wieck, after he heard her give a concert. For some years after, he was jealous of her talent, and for good reason: at a concert in 1832 his symphony was overshadowed by 13-year-old Clara’s bravura performance of a rival’s pieces before a thunderously approving audience. And then there was the fact that Clara also composed music, an astounding feat for a woman at that time. But gradually Robert’s sometimes hostile jealousy turned into admiration, respect, and love. By the time Clara was sixteen, they had shared their first kiss and declared their mutual love.

Her father played the dutiful role of the villain, opposing the union. Robert responded in true Romantic fashion with an outpouring of songs brilliantly expressing despair, defeat, exhilaration, blissful consummation. He and Clara exchanged secret letters, contrived secret trysts. And finally when Clara came of age and her father no longer had legal control over her suitors, they married. Clara continued her successful career as a concert pianist even as she bore Robert eight children, and Robert spent his time composing. It ended sadly with Robert succumbing to madness and death at the age of forty-six. But of course he left behind his immortal musical legacy, which Clara fought to strengthen and preserve even as she continued to create her own.

You could see Clara in Schumann’s music. She was immortal through him. But she, too, was Schumann’s immortality. She was the lively creature, the definite persona of the musician; he, the quiet power, the shifting identity of the composer. There was balance. Perfect, gorgeous balance.

Dobbs could hear Flora and Zeb arguing in the music room. He supposed the disagreement was once again centered on their different ideas about fame, or it might be another argument about tempo or dynamics. They had been at it all day, starting up every time he left the music room saying that he needed to work on his book. He had been having trouble concentrating in recent weeks. He stared at the painting of the Sirens, who in this rendering were a strange mix of woman and bird. Waves crashed on their rocky island; a ship approached, enthralled by their song; Odysseus tied to the mast. Dobbs was curious how and why a storm had fathered musical daughters, and wondered how exactly their hypnotic voices caused the sailors to steer onto the rocks and what they sounded like. Was it anything like Flora and Zeb? He sat on a bench, jotted down a few disconnected sentences in his notebook, then closed it with violence. The summer was scorching, but he felt alternately hot and cold. Like some sort of pathetic junkie, he thought. He tried again, gingerly opening the notebook.

Every day, Zeb asked him what he was writing. It was a good question. He had documented a few broad details of their lives, but not much else. Linnell was expecting a book, but he couldn’t clear his head. He thought only about the next time he would hear Flora and Zeb play. He turned around and stared into the conservatory. The plants undulated gently in the tanks.

Zeb’s voice meanwhile seemed to be winning the argument with Flora. Flora was strong willed, but if Zeb had a good point she would sometimes listen and concede. Lately Dobbs had noticed that when Linnell heard them arguing she smiled. He suspected that she had planted the seeds for some of the arguments. Together Flora and Zeb could challenge her, but divided she could keep each of them under her thumb.

His eyes were drawn to several photographs on the wall beside the conservatory door. Upon closer examination, he saw that they had been taken of Linnell when she was a girl. It was obvious that she was an only child doted on by a wealthy family. Linnell had been an awkwardly proportioned girl, somehow both too tall and too plump, with frizzy hair and large pimples that must have been the cause of the pitted scars on her face. Dobbs imagined her rich and unattractive, sticking with her studies because she was taunted by other kids. He wondered if she had listened to Schumann and thought of escape, of piercing through the veil and grasping whatever it was she wanted most but could never have. He could see it easily: she had been good at science, bad at music. Shut off, like him, from what she loved; shut off, perhaps, from a similar dream of Musette.

He felt dizzy. Flora and Zeb had lapsed into silence, but he could hear Linnell’s voice coming from the conservatory. He wondered who she was talking to. He held his aching head in his hands for a few minutes, then heard a noise and jumped. He looked up to see Linnell standing in the door of the conservatory, staring at him without expression. She looked disheveled, as though she had been struggling with a wayward animal.

“You’re slacking, Mr. Dobbs,” she said. “Keep in mind that you will need to complete the majority of the book before Flora and Zeb’s debut at the end of summer. Of course, I would have written the book myself, but we musicians are so specialized, and we don’t very often have a way with words.” She didn’t bother to smile.

“I hate to remind you,” said Dobbs, “but you’re not a musician – your children are.”

“And you’re not a musician either, Mr. Dobbs, are you?” she said, as she stormed past him through the hall.

His head sank back into his hands, and he sat there for a time, his vision spinning. He felt himself aching, aching for something he wanted but could never have, and didn’t even know what it was. It had become a physical pain now, like a need for sustenance.

Someone touched Dobbs on the arm, and he shuddered. It was Flora, looking frightened. He realized with surprise and terror that he had blacked out and was on the floor looking up at her. He tried to rise, but found that he couldn’t. “In some way, I need your music,” he said.

“Mum knows it, too,” whispered Flora.

Dobbs didn’t answer, but the truth of it struck him all at once. Like any addict, he had been blind to it. He didn’t know what it was about their music, but he knew he couldn’t give it up. He could not be separated from it without falling like this, without perhaps dying. He would always have to listen to the music and gaze through the veil. He was afraid.

“You have to play for me,” he said. He shook and his voice was hoarse. In the silence, he could hear the distant sound of the waves on the shore. Flora ran for her flute.

***

Dobbs let himself be supported by the coolness of the water. It was a welcome relief to his feverishness, like being held by familiar arms. He stared up into the vaulted glass dome and the darkness beyond. Since that afternoon he had been trying not to think – about the upcoming concert, about Flora and Zeb’s music, about his all-encompassing need for it. He wanted to just stay in the moment, go with the gentle lapping of the water, feel relief from the familiar throbbing in his back. He laid his glasses on the side of the pool.

“Why does he need glasses?” his mother had always asked. “Shouldn’t his eyesight be perfect? Didn’t they think of that?” After a while she had shifted her questions to him: “Why don’t you just have surgery to correct your vision?” He didn’t have an answer for her. Maybe he liked being able to put things out of focus for a while.

Flora was splashing around near him. He turned toward her and tried to show her an easier way. “You use too much energy – try for smaller, more efficient movements.”

She laughed at him and kicked away. He felt the ripples in the water reach him, brush against his body. She swam under the water, came up next to him and nibbled on his ear, though only for a second. It was the first sexual overture of an adolescent, not the more mature advance that would be expected of a nineteen-year-old, but Dobbs was aware that he was trembling. As he attempted to find a place to direct his gaze he accidentally glanced into the depths of Zeb’s knowing eyes, and Zeb laughed, apparently understanding his predicament. He was comfortable with Zeb, comfortably attracted. But Flora was more of a challenge, stirred him up like a heady stimulant. He liked both sets of feelings and felt empty when one was lacking. Linnell had been that successful, he supposed, in forming two sides of one personality.

Flora interpreted Zeb’s laughter the wrong way, and moved off down the pool, a hurt look on her face. Dobbs began to swim after her, but stopped when he heard the familiar sound of Linnell’s heels.

The door opened and Linnell strode over to the chair where Dobbs had put his towel and his notes. She picked up the notebooks. “I’ll be reviewing these now,” she said in a saccharin tone. “You just let me know when you have more ready.” Then she turned and left.

“Just like that,” muttered Dobbs. Linnell must have known that after days of hearing Flora and Zeb play he couldn’t have pulled himself away from them even if he wanted to. He was a prisoner now in a sense, a prisoner of this strange addiction, and thus a prisoner wherever Flora and Zeb happened to be. Linnell would know that even more certainly after she had reviewed his notes. Dobbs made a decision. “Escape,” he said quietly. “After the concert, the three of us have got to leave here and escape.”

“Escape . . .” said Zeb wonderingly. “How? Where?”

“I’ll figure out something,” said Dobbs. Perhaps they could go to North Bloomingville, the small college town where he went to school, and some old friends of his might harbor them. But he was determined not to take Flora and Zeb to Musette . . . Musette, where they would be exalted, and he would be left alone to die outside the walls.

5

In the weeks leading up to the concert, Dobbs planned and reviewed maps when he felt able enough, eventually deciding to take Flora and Zeb to North Bloomingville and hide them there, at least on a temporary basis. But the more he planned, the more Linnell called Flora and Zeb into the music room for private talks. Dobbs could hear her soft, motherly tones through the door, and after each of these talks Flora seemed more distant. Often her face was patchy and flushed, and he knew she had thrown some passionate fit and been crying. She didn’t laugh much anymore and her eyes were dull. Zeb also avoided him, pretending to be absorbed in practicing. There were dark circles under his eyes, and he sat for long periods with his face hidden in his hands. Dobbs wondered what Linnell had been saying to them, but when he asked them, they only forced smiles and talked about the concert. The change in them scared him. He thought perhaps Linnell had discovered his plan, but when he asked Flora and Zeb about their escape, they still expressed excitement.

Linnell began to brood as the concert approached, and disappeared into the conservatory for long periods. As Dobbs stood in the hall, occasionally he could hear her talking. At times her tone indicated she was on the phone inviting an important person to the concert, but at other times her voice was quite different – a low, soothing whisper, though he couldn’t make out the consonants. He wondered if she kept a pet cat in the conservatory, or maybe some kind of aquatic mammal lived in the tanks.

The night before the concert, Dobbs knew it would be useless to try to sleep. He prepared himself for a long evening, and walked toward the hallway with the portraits of Robert and Clara. Over the days he had gone there often to gaze at them. Sometimes he felt as though he went to them in supplication. He was especially comforted by Clara’s calm gaze. She had been Schumann’s rock in the storm of his creativity, and together they had been music incarnate.

But as he stood in front of the portraits, he became weak and shaky much sooner than he had expected, and he fell there in the hall, doubting he would be able to get to Flora and Zeb in time. He thought it might be peaceful just to lie on the floor and let go, but after a moment he mustered the effort to crawl toward the pool, where he knew Flora and Zeb were. He made his way by feel since he saw only a gray haze. He had once been poetry in motion – many people had said so when he was a diver – but that was gone now. Now he was only a cadaverous addict, dragging himself down a hallway, unsure if he could make it more than a few feet, his vision fading.

He woke held by the water in the pool and by Flora’s arms. He had told her recently that contact with the water had always given him strength when he needed it. She and Zeb must have found him in the hall and put him in the pool hoping it would revive him. Neither of them went anywhere without an instrument now, as Dobbs needed more frequent fixes; Zeb was a few feet away from the pool playing an oboe. Dobbs willed himself to climb a steep interval within the music and reach toward the veil, knowing that afterwards he could have relief for a little while.

Zeb stopped playing. “We found you outside the door,” he said. “We didn’t mean for this to happen to you. Mum never told us it would happen.” He looked burdened with guilt, older and no longer childlike.

“It happened,” said Dobbs, slipping gently out of Flora’s arms and supporting himself against the side of the pool. “I don’t blame anyone.”

Zeb and Flora looked at each other, as though deliberating whether or not to say something, and Zeb leaned down so that he could speak more softly. “We tried telling Mum that we refused to play the concert, tried telling her that we were leaving. But she threatened to hurt you.”

Dobbs thought about it for a second, then laughed. “Hurt me?” he said. “I don’t think there’s much more she can do. I’m already so dependent on your music that I can’t get further from you than the opposite side of the house.”

“Mum says that we have to leave after the concert tomorrow – without you,” said Flora, climbing out of the pool. “She says we’ll be famous.”

But while she spoke, her eyes filled with tears, and now she sat on the side of the pool, buried her face in her arms, and sobbed. Zeb said nothing, but looked away. Dobbs climbed out of the pool and sat on the edge beside Flora. Linnell meant to drive him away from them, and that would hurt him. And though right now he was here, bound to them, tomorrow night she meant to break the bond and abandon him to the storm. That alone seemed enough of a threat; but what was this other threat to which Zeb referred? He feared that it was quite possible Linnell might have some other means to punish them.

“We were trying to keep you from knowing, but we can’t escape with you now,” sobbed Flora. “We refuse to go because we don’t want Mum to hurt you.”

Dobbs felt a wild desire to kidnap them, to get them as far away from Linnell as possible. Was this how Schumann had felt about Clara when he had to sue her father for her hand in marriage? Was this how Clara had felt about Florestan and Eusebius? He could imagine the precocious child Clara inspired by Robert’s twin muses during her long hours of practice, looking forward to the talk and games, and how the idle fun had led to love over the years. But Dobbs’s addiction had grown increasingly debilitating in recent days, and he was almost too weak to move, let alone make a strong decision and escape the house.

Flora was still crying. She climbed onto his lap, hiding her face against his neck. He held her like a child. He was shaking again. He tried to think, but his mind felt thick and cloudy. Zeb sat on the edge of the pool beside Dobbs, put his arm around him and squeezed his sister’s hand. The closeness was so much what Dobbs wanted that it was almost more than he could bear. God help me, he thought. All of Schumann’s gods and demons, help. He laughed bitterly, and it rang out hollow and echoing against the glass dome. Like Schumann, maybe in the end he would just give himself over to the demons.

6

It was ten minutes to eight. Dobbs moved the backstage curtain and glanced out past Flora and Zeb into the auditorium. Most people looked annoyed and few were talking. It was a small crowd – twenty or so, mostly men. They were probably rich locals, with perhaps a few music critics mixed in. Some stared out the window down toward the dark sea . Linnell was not among them.

“Maybe I should leave until the concert is underway,” he told Flora and Zeb. He was afraid he would react with violent jealousy when they started playing for the crowd.

He left them and walked toward the hall with the paintings. Tonight he was drawn most strongly to Schumann. He tried to meet his gaze and glimpse the hints of Florestan and Eusebius. It occurred to him that Flora and Zeb were not made up only of Schumann’s disparate parts; Clara also had a place within them because she had become so much a part of Schumann. Flora and Zeb were not just composers, like Schumann, but musicians, like Clara. They had both the fiery nature of the performer and the shifting identity requisite to creative energy. But Dobbs was neither immortal composer nor performer alive in the moment. What place could he ever hope to have with them? It had been stupid to hope.

As he opened his eyes and walked back toward the auditorium, he could hear that the concert had begun. Flora and Zeb were playing their peculiar pieces that sounded so familiar and yet so foreign. Even from here he could feel a tingling energy. Flora was playing with all her determination, all her drive to be a success. Zeb played with his characteristic verve. But there was a discordant element present, a frantic edge.

Dobbs opened the door to the auditorium, and at once he saw that the addictive power of the music worked a much different effect en masse than it did upon just himself; a mob was forming. Ravenous looks deformed the faces that Dobbs could see. The members of the audience were crazed with desire for whatever it was each of them wanted just beyond the veil, and in their deluded state they thought they could somehow force Flora and Zeb to give it to them. A few people were now shoving each other aside to try to get closer to the stage. Zeb was turned away from him, but Dobbs could see Flora’s face streaked with tears. She tried to stop playing and at once, several people in the crowd roared with rage, furious that the source of their desire had vanished. An older man picked up his cane and wielded it like a weapon. Flora turned and started playing again. Dobbs felt the desire to run to the front of the auditorium and protect Flora and Zeb, but knew there was nothing he could do against so many. He shut the door to the auditorium and ran back through the hall. He would find Linnell. She might know what to do.

He didn’t think that she had foreseen this. No matter what her intentions toward him, her own children were of paramount importance to her. Her pure, if ingenuous, intention had been to revolutionize music. He began to understand that Flora and Zeb were failures, though Linnell didn’t know it yet. There would be no breaking through the veil for the masses – only a violent rage just below it, and in no more than a few months Flora and Zeb would be ripped apart by mobs wild with obsession, furious because through the music they glimpsed but never reached their heart’s desire.

But Dobbs knew his heart’s desire. It was Flora and Zeb, the veil be damned. He would continue to gaze just beyond it without ever penetrating it if that’s what being with them meant. Maybe one day he would tear it aside, or maybe he would only black out on the floor again and again, weak and shaking. But he knew now what his mistake had been; he must take Flora and Zeb to Musette, regardless of what happened to himself. He would beg, would break down the gates if he could be in that place with them. But if Musette wouldn’t allow him in, at least Flora and Zeb would be safe there. Someone in Musette would know what to do about them, and no one else would end like him, tortured by wonders he glimpsed through the thinnest of veils but shut off from them forever.

When he reached the conservatory, he found the glass door locked as always. He took the painting of Clara off the wall, used the frame to shatter the glass in the door, and stepped into the room. It was dark, and within the rectangular tanks the plants were vague and undefined. The smell was strong now – a rotten smell with a tinge of salt. Linnell stepped out of the shadows, angry. She clutched his notebooks. She started to say something, but a second later Dobbs saw the suggestion of a shape in one of the tanks, a human form that moved through the tangle of plants toward the dimly lit front of the tank.

Linnell saw it, too. “No – stay, Molpe,” she said. She looked frightened.

A head broke the surface of the water. Out of its mouth came a melodious hum which built softly at first, then crescendoed and went on and on without stopping. Dobbs backed toward the door of the conservatory, and the shape emerged from the tank. As it moved into the light Dobbs saw that its top half was covered with glossy, iridescent feathers. Its bottom half was the naked form of a woman – a woman who had reached sexual maturity very recently. Linnell had created a Siren, and Dobbs understood all at once that he was the unfortunate sailor doomed to appease her. Linnell had planned to give him to the creature after his book was finished, and had used the threat to spur Flora and Zeb to perform. He backed into the hall, the Siren and Linnell both following.

“Molpe, please . . . Molpe,” Linnell was saying over and over in the tone that Dobbs had heard her use behind the locked conservatory door. She sounded so foolish that he wanted to laugh.

Dobbs continued to back through the hall, passing the portrait of Schumann. Suddenly his addiction seemed tame to him, and Schumann’s maddening veil was an old, familiar friend compared to the ghastly but compelling noise the Siren was making. This was a sound designed to seduce and then kill. The Siren lunged, and Dobbs thought for a moment she meant to attack him, but she dashed past him toward the auditorium. Linnell and Dobbs followed.

When they entered the auditorium the crowd turned and looked at them with menace. Flora and Zeb stopped playing when the Siren appeared, and the mob was furious that the music had been disrupted. Flora stood up and stared at the Siren who inched slowly across the back of the auditorium, staring distrustfully at all of them. Flora looked from Dobbs to Linnell.

“You meant to give him to her? How could you do that?” she shrieked at Linnell. “How could you do that to us?”

Linnell went down the side aisle toward the stage as the Siren’s loathsome crescendo continued. She no longer paid any attention to the Siren, but was instead transfixed by the audience’s violent reaction to Flora and Zeb. A large man walked toward Flora with his hand raised as though to strike her, and a shorter man produced a pocketknife. Linnell ran to the stage and stood between Flora and her attackers. Despite the mob’s angry yelling, the Siren’s song seemed to gain in strength, and then began to overtake the noise. Dobbs could see each of the men fall prey to her song as her tones became compelling and reassuring, but sickly like the smell of rotting seaweed.

The large man who had tried to hit Flora made a move toward the panoramic window and smashed a chair through the glass. Dobbs could hear the sound of the sea below. Without ceremony, the man climbed onto the sill and jumped. Flora screamed. Dobbs saw Zeb move toward the window, but Flora lunged forward and held him with all of her strength. Other men in the room moved toward the window, and Linnell stood on the stage yelling unintelligibly. The Siren was steering the men toward the rocks, Dobbs realized, the rocks that lay below the window on the edge of the sea.

Then the sweet hypnotic voice started inside his own head, reassuring him that it was okay to listen. The Siren moved to the window and beckoned. Dobbs saw Flora’s desperate efforts to keep Zeb from the window, her eyes swollen from crying. He took a deep breath and threw himself against the Siren, colliding and grabbing feathers and skin. If they fell in the right way, he knew, they would miss the rocks, and would instead plunge into the inlet beyond them.

In an awkward dive, they soared beyond the jagged edges of the window toward the sea. The shock when they hit the water was almost more than his back could take. He felt the pain, but knew at once that it hadn’t broken him. He was diving again, deeper this time than he ever had before. He still held the Siren squirming in his arms. He could sense her voice inside his head, feeling for his doom, trying to find some way to ruin him. He began to lose the will to rise back to the surface and felt the burning in his lungs turn to resignation. His doom was almost locked into place; but there on the edge of those possibilities, blind in the dark ocean, he found he could still reach toward that place beyond the veil. That part of you, he thought, that part of you that they couldn’t engineer, they couldn’t touch. Beyond the veil was the place where words ended and the paradox of music lived – an expression of love, complete and whole within himself.

He grappled with the Siren for what seemed like a long time, but he knew he was the superior swimmer. In the dim water he had lost all sense of rhythm and time, but at last he felt her weaken and give in. She seemed then to change into a different form, akin to the rocks along the coast. He felt himself being pulled down by the sudden weight. As he let go, he watched her form sink and disappear into the murk.

When he broke the surface, the salt of the air filled his stinging lungs, so that he wasn’t sure for a moment if it was really air he breathed or the water from the sea. He saw that the waves were choppy. A squall was blowing in.

***

Dobbs scrabbled up a rocky hill and returned to the house. He found Linnell, Flora, and Zeb barricaded in the domed room with the pool, safe from what remained of the clamoring mob. He entered through the back, and Flora and Zeb ran to him at once and embraced him. But it was Linnell that Dobbs looked at. She sat on a chair staring straight ahead.

“Molpe . . .” she said softly. After a while, she looked up. She still had Dobbs’s notebooks in her hands. “We can’t break through the veil with Flora and Zeb,” she said.

“Later,” said Dobbs. “Later, there might . . .” but his voice trailed off. He wanted to reassure Linnell, to somehow comfort her, but he couldn’t be certain about anything now. And he was not about to invite her to come with them to Musette. She held his notebooks out to him, nodded curtly, and walked outside toward the back entrance of the dark conservatory.

Dobbs sat down by the pool and began telling Flora and Zeb the truth about Musette and the expedition they would have to join.

7

Dobbs had lost his glasses in the dive, so they took a cab. They packed light, Zeb carrying his violin and Flora her clarinet, and sneaked out the back under cover of night to avoid the still angry mob. As they climbed into the back seat of the cab, Flora put on sunglasses to hide her puffy eyes.

“I don’t think your addiction has a cure,” Zeb said as the cab pulled away.

“We’ll just keep trying to do something about that veil,” Dobbs said with a note of optimism in his voice that had long ago died in his heart. He couldn’t remember ever feeling this tired before.

“Mum failed,” said Flora.

Dobbs shook his head. “No – Romanticism hurts. That’s just the way it is. Your mother is as much a Romantic as Schumann. She created the two of you to be daring and original, and our lives will be anything but unoriginal.”

Zeb managed a laugh. Flora fidgeted between them in the middle of the backseat, and Dobbs could see that something was bothering her, in fact had been clearly bothering her ever since he had told them selective details about Musette – the details that he hoped would most cheer them.

“You told us Musette was for musicians,” Flora said presently. “But you’re coming there, too – aren’t you?”

Dobbs smiled at her, squeezed her hand, and tried to reassure her by exaggerating the compassion of the Musettians.

“In that case, Musette will be nice,” she said in a small voice that shook a little. “It’s a pretty place. Isn’t it? Trips into town to see the locals and do a little shopping. And just a simple house somewhere in the country where we can play for you without being overheard.”

Dobbs did not correct that vision. If it made her happy, he would let her keep it.

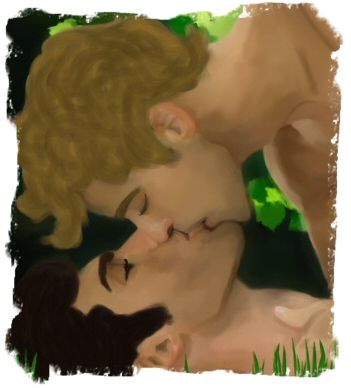

She looked at Dobbs over her sunglasses. He saw how scared she was. It was all so new for her. He leaned over and kissed her on the lips. She smiled and pushed the sunglasses back up the bridge of her nose. Zeb nudged him, and he kissed him, too, not caring what the cab driver thought. Then he sank down in the seat, praying that he would find a place for them in Musette and that no one else would get hurt.

He felt an ache and trembling that was all too familiar to him now. Soon he would have to reach again toward the veil, and fall and falter, life and limbs failing him again and again.