By Kam Oi Lee

There was a hole. I was the only one who could see it. And every time I looked, a few more rocks went tumbling away into the bottomless darkness below.

“Well?” said Morgan, poking a finger at me through a tear in the screen door. “Are you going to the game with us, or not?”

I shifted my bare feet on the kitchen floor. I thought about telling him I didn’t even like football anymore. It would be easier than talking about how I couldn’t go anywhere without people staring and whispering. But Jesus, everybody liked football. If I said I didn’t, that was just one more piece of evidence against me. Besides, I did like football–even though I hadn’t played in a while because nobody wanted me on their team anymore.

“Eva says she’ll bring her sister. She says you’ll like her.”

Eva. Morgan had Eva, she was his evidence. That was why none of my troubles had rubbed off on him. That was why he could say the things he said at school. Things like, “Leave Andrew alone! He’s just a regular guy like me or anyone.”

I wouldn’t like her. That was the whole problem. “Haven’t asked my Ma yet,” I muttered.

“So go ask her.” He gave me a pointed look. “Everybody else is going,” he added.

The hole yawned at my feet. I wanted it gone–and at the same time I wanted to keep it and hold it close. Wanted to struggle and fight for it because it was mine.

I clamped down on the longing, and forced it away. The hole had to go.

#

“You may go to the game,” Ma said finally, after one of those long silences she always seemed to hold on purpose.

“Thank you, ma’am.”

She fixed me with an icy stare. I felt it drill straight into my stomach. “But you’re not to speak to that Dirk,” she said.

I hadn’t spoken to Dirk, not since that day. I’d blown my only chance. I had been passing through town on my way to school when I saw him approaching with his long-legged, loping walk. For an instant, I’d wanted to run to him. Instead, I’d backed into the doorway of the hardware store, but not before I got a glimpse of bruises and a freshly blackened eye.

“He won’t be there,” I said, trying to stare back at her just as coldly, and failing as usual. I will not think about Dirk. I will not think about him…

“And you’re to behave properly, Andrew. No fighting.”

“Yes, ma’am.” Fighting wasn’t going to be a problem, not anymore. Nobody wanted to touch me, not even at the end of a stick. Everybody was afraid they’d get whatever it was I had.

She glanced at her watch. “It’s time to leave for our appointment,” she announced.

“I don’t want to go see anybody,” I snapped at her.

“Son, don’t you backtalk me. Get your shoes on. Don’t make this situation worse than it is.”

#

At least the preacher wasn’t afraid to shake hands with me. I guess he figured he had Jesus on his side.

“You know you look just like your Pa,” he said, as he beckoned us into his office.

I nodded. “Yes, preacher. Everyone says that.” Pa died when I was five. They say I inherited his looks. I sure didn’t get his personality or his sense of humor.

The preacher looked at Ma. “All right if I speak to him alone?”

She nodded her assent. The door closed behind her.

“Sit down, Andrew. You understand that what happened wasn’t your fault. Don’t you?”

“Yes,” I said.

“Good,” said the preacher. “You should also understand that Dirk isn’t evil. He’s got a sickness. Not of the body, but of the mind. And when people are sick in that way, they seek out other people–to pull them over to the other side, so they’ll have company. That’s what he was trying to do to you.”

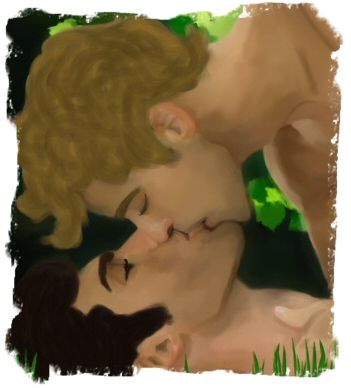

“Yes,” I said, and found the edge of the wooden chair, and clutched it. Remembering: a perfect day at the swimming hole, and then later, the abandoned house with the sun streaming through its windows; Dirk with his shock of blond hair and that crooked smile that was only for me; the warm, rough touch of his hand against my face; the rush, a charge like something electric leaping and soaring inside of me, and the distance between us that got smaller and smaller. Nothing else in the world mattered, nothing except for closing that gap.

“Your Ma tries hard to be both parents to you,” said the preacher,” but with your Pa gone, there’s no man in the house for you to look up to, which makes you more vulnerable to people like Dirk. That’s why it’s important that you stay far away from him–because you don’t want to turn out like him. Do you?”

But I did. I’d admired him, thinking: “That’s what I’ll be like. Just give me a couple more years.” I’d followed him around, puppy-like, until his college friends teased him: “What is he, your little brother?” Whenever he asked, in that slow, soft-spoken way of his, if I wanted to go fishing or swimming, the words were hardly out of his mouth before I’d say yes. My heartbeat would kick up at the sight of him, like a sudden gust of wind. Like he was a spark and I was a dry leaf waiting to burst into flame.

“Do you?” the preacher repeated, and his voice was soft, but he was looking at me hard, like he could see into me.

I gripped the edge of the chair. I swallowed. It felt like gulping a mouthful of nails. But I was going to the football game: Eva would introduce me to her sister, and I’d like her.

I looked him in the eye and said it loud. “No, preacher,” I said, loud and clear.

Ma frowned at my dinner plate. “Stomachache,” I mumbled, and rose from the table quickly, before she could scold me about how it was a sin to waste food.

Upstairs, I pulled the knife from under the mattress of my bed. Ma didn’t know I had it. She would never have let me keep a present like that, no matter who it was from. It was a four-inch blade with a polished wood handle. It must have cost him a lot of money. At the base of the blade were my initials, engraved in block letters: A.J. Only Dirk ever called me A.J.

But the gap had never closed. It was still open, even now. His college friends had stumbled on us at just the wrong moment. He’d stood there frozen, his blue eyes wide, like a startled deer trapped on the road at night. I twisted out of his embrace and backed away from him like he was poison–but the disgust on their faces said they knew.

They dragged us both outside, under a maple tree. “Dirk, we’re going to teach you a lesson once and for all, you fucking pervert. He’s just a kid!” And when I struggled, trying to turn away from the dull thud of the blows and the sight of the blood running down his face, they said, “No you don’t, little Andrew. You’re going to watch what happens to faggots.”

Finally they let me loose: “Go home!” I ran. And then the next day it was all over town. Everybody knew. There had been rumors about Dirk before, but this was evidence. They’d all seen us together. All I ever got from him was a kiss, but it was enough. It of proved what he was. And what did that make me?

I pulled the knife halfway out of its sheath, so that I could see my initials. If only I’d been carrying this knife on that day.

But it was his fault. Why’d he have to go and pick me? I never asked to be pulled over to the other side. I never asked for any of this.

Bastard. I’m not like you.

#

“You’re to come straight home after the game,” said Ma.

“Can’t I go to Morgan’s house afterwards?”

“You’re to come straight home after the game.”

I slammed the front door on my way out. Ignoring the resulting yell, I started walking as fast as I could in the direction of the college.

I hadn’t gone a quarter-mile before Morgan came running towards me, raising a cloud of dust behind him on the dirt road.

He skidded to a stop in front of me. “I don’t want to go to the game,” he gasped. “Let’s go back to my house.”

“Morgan, are you kidding? You bugged me and pestered me, and now you don’t want to go?”

“I changed my mind.” He cast an apprehensive look over his shoulder. “Let’s go to my house, Andrew. Come on!” He was pulling at me, tugging at my arm.

“All right, Morgan. Fine, we’ll miss the game. Since you’ve decided to go crazy.”

And I let him pull me to his house. We sat upstairs in his bedroom and played checkers. He avoided my eyes for the most part. When he did look at me, it was like he was searching for something. Like he was afraid he was going to find it.

Then Ma came over and got me. She towed me back home with such a grip on my arm, I thought it would leave a bruise. The instant we were inside the house, she turned around and whipped the front door shut, like she thought somebody might be following us.

“Sit down,” she said tersely, motioning me into the living room.

“Ma, what’s going on?”

“Just sit.” She gestured impatiently at the sofa, then sat down on Pa’s stuffed chair. “The game has been cancelled.”

“Cancelled? How can it be cancelled?” Maybe there was an emergency. “Is there a storm coming?”

“No, son, there’s no storm. There’s trouble, up at the college.” She clenched her hands in her lap. “Andrew, I’m very sorry. They found Dirk, a little while ago. He…”

I did sit down on the sofa then. Or rather, I fell there. My legs felt like they’d been chopped out from under me. The bottomless chasm opened up in front of me again, darker and more vast than ever before, while her voice dwindled to a vague buzzing in the distance, with only occasional words sticking out: “body … the rope … took his own life”.

I don’t know how long I sat there. Eventually I started hearing Ma’s voice again. “Andrew? Andrew, look at me. He was a very troubled person. I’m sure no one meant for this to happen.”

“The hell they didn’t!” I shouted, and leaped off the sofa, but she was quicker, blocking my way to the front door.

I stared her in the face. I was taller than her. I had to look down to meet her eyes. I knew what she saw when she looked at me: a disobedient child. But I was sixteen, dammit. Sixteen was almost a man. She could only keep pushing me around if I let her. Get out of my way!–but I couldn’t get the words out.

“Son, don’t you swear in this house,” she said quietly.

“You can’t keep me here forever!”

“Go upstairs,” she ordered. “Now.”

I mounted the stairs, feeling her gaze boring into my back, cursing myself for not having the balls to run out the front door. Instead I was going upstairs to my room again, like a helpless little kid. What was she going to do next–turn me over her knee and whack me with Pa’s belt? I reached the top of the stairs, made a left into my bedroom, then let out a yell and slammed my fist into the wall.

Ma was there in two seconds flat. She bawled me out while I clutched my hand and stared at the wall like I could put another hole in it that way.

“You are not to leave this room,” she finished. “And you will fix that hole in the wall tomorrow.”

She marched downstairs. I sank onto the bed, breathless, feeling my throat close up. There were two rules in Ma’s house–no swearing and no crying. I broke the first one frequently; the second one, never.

Morgan had known. He had been trying to keep me away from town, so that I wouldn’t have to find out from random guys in the street that “Dirk the Assrammer” had decided to off himself. And it was my fault. If I had been the friend he thought I was, if I had stuck by him instead of staying away like I was told, then he would still be alive. How alone he must have felt, just him and the rope.

Ma came back upstairs with some ice wrapped in a towel. Later, I was allowed back downstairs for dinner. My right hand was next to useless–I had to hold my fork in my left. Not that I felt much like eating. I had a tough time swallowing anything, and then it all sat there like stones.

“I heard from the neighbors,” she said. “The funeral is tomorrow.”

“Could… Could I go to the funeral?” I said.

She shook her head.

“Please, Ma.”

She sighed. “Andrew, I’m not quite as heartless as you think I am. The reason you can’t go is because people might not want you there.”

I dropped my fork, let it clatter onto the plate. “Oh, I see. You think they’d blame me,” I said bitterly.

She wouldn’t answer me. She just pressed her lips together in a line.

I was sent back upstairs right after dinner. Sleep was impossible. I sat at the edge of my bed in the darkness. There was just enough pale moonlight that I could make out the hole in the wall.

Ma’s words kept coming back to me. How could she know they wouldn’t want me at the funeral? She just didn’t want me to go, for the same reason she didn’t want me to go anywhere, not even to the corner store–because she was in charge. And I wasn’t going to take it anymore.

I would find out where the funeral was being held, I would go there and stand by him even if he was beyond needing me. People could look at me sideways and call me whatever names they liked. As if a bunch of lousy words would stop me from paying my respects! And if anyone wanted to fight me, I’d give as good as I got.

But Ma was a light sleeper; there was no way I’d sneak down those stairs without her knowing about it. I could climb out my window and slide down the drainpipe. No, I’d need both hands for that. Maybe I should forget about sneaking and just bolt down the stairs and out the door. But then I just sat there, paralyzed by how everything hurt: my hand, my stomach… And that gaping abyss.

At last, I pulled the present he’d given me from its hiding place. I would only need one good hand to use it. Oh Jesus, Dirk. I’ll never see you again.

#

It was full daylight, and Ma was calling to me up the stairs.

I shoved the knife back under the mattress. That was where it belonged. Walking downstairs took forever; my body felt like it was made of lead and at the same time unpleasantly light. I almost tripped on the bottom step.

But if my body was being uncooperative, at least I had my head together. If they thought I was like him, if they thought I was going toslit my own throat and leave my body behind as the final damning evidence, they were wrong. I knew how to deal with a hole that was just too big to fill. It was simple. Just put a wall in front of it, so I wouldn’t have to look down there anymore… So I could never fall in.

Ma leaned out of the bathroom door and into the hallway. She was dressed in her best, right down to her Sunday shoes. “I’ve been calling you for fifteen minutes, and you’re still not ready,” she said, with a sharp frown at my pajamas. “I’ll ask the doctor to look at your hand after church.”

“Yes, ma’am.” I leaned my shoulder against the bathroom door frame. It was solid, comforting.

She turned back to the mirror, patting her hair. “Well, hurry up and get dressed. We’ll have a quick breakfast so we’re not late for the service.” Then her voice softened, and she added, “So you can pray for your friend.”

I closed my eyes. I felt dizzy, and inside me was a burgeoning ache, a dreadful sense of something shifting and turning.

“Andrew, I said to go and get dressed. Are you listening to me?”

I shoved her out of the way and sank to my knees, overcome by a surging, wrenching nausea. My right hand struck the porcelain but the pain felt far away. I don’t care about you, you bastard. I never cared. Then there was nothing except Ma’s cool hand against my forehead, and me letting go, over and over.

“Your friend,” she said.

That was a test, and the wall held. Now all that was left was to maintain it, to seal the seams and keep it intact forever. That wouldn’t be easy, but it wasn’t impossible. I could do it. I would learn how.

Pingback: More and yet more | wildeoats

Pingback: Author Interview: Kam Oi Lee « Read. Write. Edit. Publish.