by Bosley Gravel

Illustrated by Rowan Lewgalon and by the author

Jon Quiddity watched the women peel the green and blue skin away from the pink flesh with their obsidian hatchets. A group of hunters also watched them butcher the beastly wivern. Jon stood apart from them, but he was close enough he could hear their halfhearted complaints of the size of their kill—so skinny, bony, and light. They had decided to drag it the few miles from where it had been found, already weak with hunger. Their faces were still painted from the hunt. They watched and discussed the fact the wivern herds were in decline.

“Berries, roots, and salamanders. I’d sooner starve,” Walter said.

“There is no mistaking the scarcity,” another replied. This hunter was named Gavin. Gavin was lean and muscular—no fat, just sinew, nerves, and bones. He rarely wore a tunic. He was browned from the sun as meat on a spit was browned by the fire. Jon sometimes had erotic dreams where he kissed Gavin’s chest and washed his dusty feet after a hunt… sometimes there was more, much, much more. Despite the taboos of these things, there was no shame in the dreams, not for Jon. All the same, he kept them to himself. His mind was all his own, and he took pride of how he kept this secret from everyone—even the tribe’s sagacious mogul.

Walter sighed to indicate he was unwilling to commit to any speculation on the topic of scarcity. The older women with gnarled knuckles and hunched backs began to stack wood for the fire. The younger women would roast what meat there was, then make soup from the bones. Even the acrid fat between the skin and muscle would be boiled for broth tonight.

The hunters’ mates would use the mogul’s concoction to purge the poisons from the meat, all but the liver. The chief hunter must eat from the liver. He had built an immunity to the poison, hunt by hunt, since he was a child. Each kill brought a larger bite, and each bite brought him closer to the final sleep. He had misjudged the portion last year and spent three days in a kind of sleep where he could not move, but his eyes were open, and he could remember all that had transpired—the presumed fate of anyone who ate meat that was not purified.

“Any food is better than none,” Walter said finally, and then to Jon: “Go help the women, Jon Quiddity. Make yourself useful.”

Jon was the apprentice and caretaker to the tribe’s doddering, one-eyed mogul, Koan. Koan was neither man nor woman, but both. From birth, telltale organs had been twisted into an undifferentiated mess of tissue. Jon knew this because he helped Koan with his toilet every morning. Koan had told Jon that in his youth he lived as a female and often took men to his hut, and even mourned the loss of the moon with the other women. After her fiftieth year, Koan grew whiskers on his face, fine white fur like the now extinct snow munkee.

Jon looked over to Koan, who was mixing water with a previously prepared powder to create the solution that would be used to cleanse the meat. This was one of the few skills Koan possessed that was truly useful. Koan had taught Jon many things over the past decade, such as cunning sleight of hand and how to fall into a spirit swoon and speak gibberish. Koan had taught Jon to always reply in unanswerable riddles and thus appease the tribe’s need for mystery. He had taught Jon the unquestionably earthly secrets of how to calm with herbs, how to excite with herbs, and how to heal with herbs. Koan did not believe in the existence of Eleeoka, God of the Sky, Lord of Embers, nor the lately unfashionable Earth Mothers, nor the old spirits that haunted the woods and wastelands, yet he preached all their wrath and pleasures.

Koan’s first lesson was the tribe’s need of gods and moguls; the second lesson was that gods and moguls were illusions. One didn’t exist, and the other kindled ignorance and fear for his own gain.

“I said go, Jon Quiddity. I find your leering presence distinctly unpleasant,” Walter said sharply.

Jon nodded and, without making eye contact, went to help the old women stack wood.

###

Autumn shed its yellow and orange wings from the brown bones of the woods. As Walter had speculated, kills became farther and farther between. Despite the fact he would rather starve, Walter joined in the frequent meals of roots, berries, and salamanders. When winter came in earnest, they resorted to eating the white snow hares that were considered unclean. Jon found the hare meat more appealing than the piquant wivern flesh. Hare meat tasted of the summer winds and monsoon rains.

In the shortest days of winter, Koan took ill with a fever and cough. Jon harbored conflicting desires to see Koan find his final peace and to continue living in the safety of his tutelage. Jon had little affinity for the ambiguous she-man charlatan, but he deeply feared taking on the role of mogul. Despite genuine attempts, Jon had garnered no respect from the tribe. He spoke insincerely of the gods. He did not learn his lessons on healing plants well, or the tedious ceremonies. And thus far, for reasons that were not clear, Koan had steadfastly refused to share the secret of cleansing the wivern meat. Even now, on his deathbed, he would not speak of it.

When Jon asked for the final details, Koan said, “There will be no wivern, soon enough. The summer has no flame so the winter does not bite. The world is not what it was.” A froth of blood-tinged sputum stuck to the corners of his mouth. Tiny jewels of yellow mucus hung off the lid of his good eye; the same jewels crusted his nostrils. “A mogul can be a tribe’s destiny or their downfall. I am both.”

“We will starve.”

“You will not starve, and I will not tell,” Koan said.

Fury welled up in Jon as he knelt on one knee in front of Koan. He grabbed a handful of Koan’s prayer beads, pooled around his throat, and pulled him from his bed.

“Tell me!” Jon said.

“I will not live much longer,” Koan said.

“I know most of the recipe,” Jon said and let Koan slip back into his blankets.

“Better to admit your ignorance, apprentice.”

Jon stood, spat in the fire, and left their hut.

Outside, he looked over the treetops to the waning gibbous moon. Dawn was coming soon; he could smell it in the air. He shivered. A cloud passed across the slice of yellow. He pretended it was a wivern shadow. He intended to spite Koan with the image in his mind. There will be no wivern, soon enough. Jon had never felt so alone, and his had been a life of grievous isolation.

Behind him, he heard a twig snap—Gavin, lean and alert. His thin tunic fluttered in the cold air. He and the other hunters spent the long winter nights chewing dried cojo leaves. The herb caused a heightening of senses, a wakefulness, a forgetfulness. The hunters played dice carved from the last joints of a wivern tail. Often the games ended in violence and open gashes. Jon watched Gavin and became lost in his graceful form. Gavin was everything a man should be, everything that Jon was not. Jon did not realize how lost he was in Gavin’s beauty until Gavin broke the spell.

“I see you, Jon Quiddity, staring at me—”

“I see you, Jon Quiddity, staring at me—”

Jon looked away. He flushed, glad for the darkness.

“—looking at me like a woman in her season.”

“I—I, that is not true,” Jon said. Gavin came close, and Jon could see the reckless gleam of cojo in Gavin’s eyes.

“I’ve had them all,” Gavin said. “In all the ways that Earth Mothers will allow…”

Jon said nothing as Gavin cited the ways that Earth Mothers would allow.

“… in their mouths. I see you looking at me, Jon Quiddity, like you want my root in your mouth.”

Jon had spent short minutes in the middle of the night, his own root in his hand, thinking of just this. He was terrified at the thought of it happening in the here and the now. He was ashamed that his lust was so obvious. He feared Gavin’s interest might be a cruel trick.

“I grow sick of these needy sluts,” Gavin said. He stepped forward and put his strong hands on Jon’s shoulders. “You’re trembling. I know you’ve practiced your perverted talents on Koan. Everyone knows that. Don’t be afraid, apprentice to the mogul.”

Jon was bewildered by the accusation but did not want to contradict. Gavin gently pushed Jon to his knees. Jon’s heart thumped so hard he could feel it pulsating through his body. Gavin pulled down his pants. His root smelled of salt and musk, as feral as any wild animal. Jon breathed his warm breath on it, which instantly brought the desired results. The tip protruded from the ragged foreskin with a particular smell unlike anything Jon had ever smelled. Hunters were cut, apprentices to the moguls were not—there was novelty in what he saw because it was so unlike his own. Jon took it into his mouth as Gavin put his hand on the back of Jon’s head and thrust. Jon took his own root into his hand, and the moment became perfect. Jon was lost in the perfection.

###

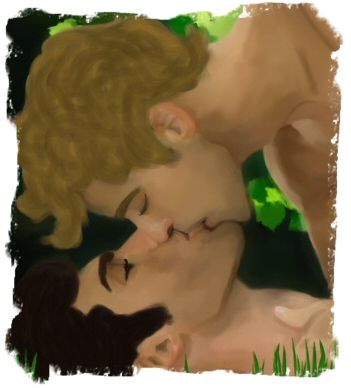

When they were done, Jon was disoriented and empty. He wanted to touch his lips to Gavin’s neck and cheeks. He wanted to thank him. He sensed these things would offend and annoy. Instead he said nothing and watched the darkness of the woods.

“This is a secret,” Gavin whispered. “A secret between you and me.” The whisper was like the edge of a knife. Of course it was a secret, of course. He knew how to keep secrets.

“Yes,” Jon said. “I will never tell—”

“Not even to the mogul?”

“He’s on his deathbed,” Jon said. “Delirious from a fever. He won’t last days.”

Gavin grunted a noncommittal response and, without apparent consideration, turned his back and walked away. Jon tied the drawstring around his waist and brushed dirt and dampness from his knees.

###

Koan lived, not days, but weeks. Night after night, Jon begged, threatened, and wept for the final steps of purifying the wivern meat, Koan refused. This night as he motioned Jon close, his voice was the last voice of an autumn wind. Outside at the edge of the woods, Gavin waited in the shadows for their weekly tryst. No wivern had been killed since the monsoons. Jon knew Gavin was wrought with tension because of this. He would be angry at Jon’s lateness.

“Mogul—the recipe.”

“Do you know what sentience is?” Koan whispered.

“No,” Jon said. “Your silly riddles will damn us all.”

“Being. Consciousness. The wivern can speak. They can know, they can love.”

“I don’t understand.”

“The wivern are as sentient as you or me. They can pursue their dreams, they mourn—” Koan fell into a coughing fit and didn’t regain his voice for minutes. Jon held the mogul’s head. Finally, he spoke, “We should not eat them. The hunters know. Ask them what the wivern say. Ask them if wivern are ready to become meat in our kettles.” Koan calmed a chest spasm. “I will not tell. I will never tell. This is my mark on this foul world.” His cloudy eye rolled back into his head, and he twitched one final time and was still. The crackle of the fire became the loudest sound.

Jon leaned back on his haunches, and a desperate feeling of powerlessness hit him. The idea of eating a sentient creature disgusted him; the idea that Koan had died without giving up the final secret terrified him. He thought of Gavin waiting in the woods for him. He wondered if he could find comfort somewhere in Gavin’s engaging demands.

The hunters know… Ask them if wivern are ready to become meat in our kettles.

Of course, Jon thought, Koan was lying, or perhaps lost in delirium due to the sickness. Jon decided he would ask Gavin. He looked at his teacher. His good eye was still open. He was thin, emaciated, little more than skin, bones, and his oddly furry face. Jon got up, took the mogul’s best robe, and let himself out into the chilly night.

Outside, a few tiny snowflakes blew across the path. Gavin was there, as he had been. The last two times he had not been chewing cojo leaves. Even that was becoming scarce. Without the influence of the intoxicant, there had been an awareness in their acts that Jon hoped could be nurtured. This sort of relationship would be tolerated between a mogul and a high ranking hunter, especially if it was concealed from the elders and the children. Perhaps only a silly daydream, but the thought was pleasant.

Gavin had built a small fire, and he squatted, leaning forward on his knees. He heated tea in a horn-shaped cup carved from a wivern tooth. Jon loathed his own weakness as the fear welled in his chest. He tried to find the words to say that Koan had passed to the next world.

“You are mogul now. The tribe looks to for strength, for… magic,” Koan’s voice whispered.

There was no comfort in the thought when he remembered he did not know the mogul’s secret of purification.

“He’s dead,” Jon finally said. Gavin took the steaming drink from the flame and sipped. He grunted a dismissive acknowledgment.

“I am the tribe’s mogul. But… but…”

“But?” Gavin said.

“Koan said that the wivern are sentient. Is that true?”

“What does that mean?” Gavin asked. He was incurious, uninterested.

“That the wivern are—they are alive. No, they are aware, not like animals. Are they like us?”

Gavin chuckled.

“Yes, it is true. You didn’t know that? All but the women know.”

Despite his coat, a burst of cold wind caused Jon to tremble.

“Then why do we eat them?”

“Because we need meat,” Gavin said. He looked perplexed at the question. “Come to the fire, mogul, and warm your hands and mouth.”

Jon came close to the fire and squatted like Gavin. He put his hands close to the flames.

“Can they really speak?” Jon asked.

“Oh yes,” Gavin said. He put his own warm hands on Jon’s neck.

“What do they say?”

Gavin considered as he handed Jon warm tea. “What any of us would say. They beg sometimes. Some of them strike out with vile, magical curses. Some accept their fate with the courage of a man and sometimes more. But I am not here to talk of how wivern choose to die.” He leaned over and took his root from his pants.

“The mogul is dead,” Jon said again. “And he did not… ”

Gavin ignored the desperation in Jon’s voice.

Jon went to his knees. Last week Gavin had taken Jon from behind, as if he were a woman. It was frightening and exciting at the same time. It took three days for the gentle ache to stop. In his current state of mind, Jon did not want this distraction, yet paradoxically, it was the only thing he wanted. The mogul lay dead in their hut—Gavin was oblivious to all but his root. Jon looked up and took Gavin into his mouth. Seconds later, Jon felt a soft but swift tap against the back of his head. He thought at first that Gavin had slapped him for a toothy indiscretion, but the sensation came impossibly to his lower back. He looked to Gavin, who pulled his root away and glared into the darkness of the woods. Jon looked down. Pinecones—someone was throwing pinecones. Then a pathetic but icy snowball hit Jon in the chin. Another snowball shattered to dust against Gavin’s chest.

“What’s happening?” Jon asked. His thoughts were dark with speaking wivern and the mogul’s corpse.

“What’s happening?” A mocking voice came from the shadows of the woods, then a round of tittering laughter. Walter and several other hunters stepped out of the shadows. They had pinecones and snowballs, and one of the young hunters had a handful of small stones.

Gavin looked afraid and terribly unreal in his vulnerability. He groaned, and the hunters sent another volley of pinecones and snow. How long before the stones? Jon thought. He wanted to run and hide. Then a thought of the mogul’s corpse came. What was he thinking, coming here instead of going to the elders?

The hunters giggled like children who had discovered dogs rutting. Gavin was wild now. Finally, he found words:

“What is happening?” he said loudly. He glared at Jon, who still knelt. “How did I get here?”

The hunters laughed harder than before.

“This mogul has used a glamour. He appeared to me as an Earth Mother! Sorcery, trickery!”

The hunters were silenced as they pondered the likelihood of this new information. Jon stood. He wiped dampness from his lips. He mumbled, imploring forgiveness, and then met Gavin’s eyes. There was some softness in Gavin’s reply, but it was partial and withheld, hidden behind his hunter’s scowl. The hunters earnestly discussed the possibility of magic—with mixed belief.

Gavin took Jon roughly by the shirt. He jerked him so hard Jon’s feet left the ground.

“What did you do to me, mogul?” Gavin asked. “Why did you cast a glamour?” Then in a whisper between his clenched teeth, “Run, I will keep them here. Run and do not look back.”

Gavin pushed Jon away, and Jon stumbled from the momentum, but he did not fall. He ran—despite the anger at himself it caused—he ran. Conjuration or not, a hail of pinecones, snow, and pebbles whizzed past him as he fled, followed by a bray of unkind laughter. Only the laughter found its stinging mark. Despite Gavin’s warning, Jon did look back. Gavin was among the hunters. He gestured in animated sweeps of his arms and hands, no doubt as he described Jon’s seductive glamour.

Ahead was the hut he shared with Koan. Somehow it had been discovered that the mogul was dead. The elders congregated in front of the hut. Some paced nervously; others exchanged bits of conversation. Jon did not stop. He pushed passed them despite their questions and almost comical squawks of protest.

Inside the hut, the fire had not ventilated properly and smoke hung in the air. Koan was unmistakably undone. His eyes were sunken, and his body was unnaturally swollen with death. Jon chose a wivern-leather bag. The skin, when properly cured, was nearly indestructible, impervious to dampness, to fire, to wind, sun, and rot. He put a change of clothes, some hoarded dried apples, a salted tuber, some herbs, and a string of favorite prayer beads into the bag. He looked around once more, then took the mogul’s unused supply of cojo leaves. The herbs would bring much-needed stamina.

The elders were at the door, afraid to enter because of the corpse, Jon realized. The bone-breaking ceremony and sky burial would be his responsibility by tradition. There would be no succession today—or ever. The elders were clearly confused by Jon’s packing.

Outside, he spoke as he hoisted the bag onto his back. “I’m leaving,” Jon said. The dim light hid the details of their reactions.

“To break his bones?” one of the elders asked.

Jon shook his head. “No,” he said. He fought the urge to elaborate.

“What? How will he abandon his body if you don’t break his bones?”

Jon, despite his obligations, was unable to reply. He felt tears well, his throat lump, a stab of bitter helplessness come to his belly. Jon shouldered his bag and stood tall. He owed them no explanation; the hunters would have explanation enough. The tears finally came, and he made eye contact with a clot of wrinkled faces that seemed to be a scene from one of the mogul’s smeary ocher illustrations.

“I am not the mogul,” he said.

Many seconds came and went.

“Jon Quiddity is a coward,” another of the elders said, an old woman. The matter-of-fact intonation of the old woman’s voice was painfully authoritative.

“Yes,” Jon said and pushed through the crowd. “I am a coward.” He was taken by how frail they were, how old.

“Who will purify the wivern meat?” one shouted in frustration.

Jon wondered if he didn’t reply out of cowardice or spite. Or if he was fleeing for those same reasons.

He walked fast, toward the far side of the village. Into the darkness just in time—behind him the hunters came in a great mob and mingled with the elders. It only took minutes for the hunters to sour whatever dignity might have remained in the gathered tribe.

Then the mogul’s hut was on fire. A superstitious hunter had indulged his fear that the mogul would become a revenant—a living corpse with the power to cause disease in every person he knew the name of in his life. The flames leaped and illuminated the entire village boundary. Jon looked once and kept going, only to see the flames jump from the mogul’s hut to the one next to it.

“The apprentice takes his revenge by spreading this fire with magic!” The gruff voice of a hunter carried, unnaturally clear, across the woods. Jon ran; they intended to give chase.

Once in the darkness of the woods, he could hide among the shadows. The thought of spirits would keep them from chasing him far, and despite the scarcity of wivern, the hunters feared coming upon them at night. He made it to a familiar crook in the path, and then another. He felt free for the first time in many, many years. But it was short lived—something wrapped around his throat and pressed against his mouth. His lips bruised as they were ground into his teeth.

Gavin slammed Jon up against a tree.

“Stay away from paths and plains to the south. It is Hanalei, a wasteland. To the west is the sea; then go north,” Gavin said, his breath sour, “but carefully. That is Quemazon. There the earth still births wivern.”

The hunters believed that wivern were born as eggs from molten pools of lava and pushed up through volcanic shafts, then carried to their nests, hidden in cracks and crevices in the mountains. It was untrue, Koan had taught Jon, but he’d warned to never contradict the hunters. Jon shook his head in the affirmative, but he still could not speak because Gavin had his hand pressed so tightly to his mouth.

“The tribe will kill you if you come back. You’re a curse embodied. I will kill you if you come back. Go now instead.” He let go of Jon’s mouth and clumsily embraced him. Jon’s breath was gone, and Gavin did not wait for it to return. “Run, you cowardly faggot who seduces with glamour!” Gavin shouted. Jon sprinted ahead, fear driving him hard.

Behind him, the mob caught up to Gavin. “He’s run south, to the wastelands, to walk among the unholy spirits.” Jon looked to the moon and then to the North Star. He slipped off the path and headed through the trees, opposite of where Gavin had directed the mob.

###

Some nights, Jon felt the woods belonged to him and he to the woods. Not this night. Tonight he pushed one cojo leaf after another into his mouth. They were rough and had an earthy, minty taste. The juice would first numb the jaw, then excite the heart, then give energy to the limbs. Too much might cause cramps and vomiting. Jon did not care for recreational use of the cojo leaf, but he sometimes chewed to keep up with Koan and his uncanny ability to go for days without sleep.

Jon looked again to the North Star, a streak of gold ejected itself—a meteor—Semen of Eleeoka, Lord of Embers. Jon did not believe he existed. When the stroke of fire burned away, the North Star was unchanged. While he did not believe the sky sparks were divine, he did not speculate as to their true nature. Not tonight, not with the cojo working its way into his limbs.

He tightened the straps of his pack and experimented with an accelerated pace. He found it to his liking.

A final look at the valley below—fire blazed in the village, smoke blew in knotted streamers. In the past, the wivern were so plentiful their herds sprung wild through the woods at night. They had often attacked and purged the villages with fire. How long ago had that been? Not since Jon was a child. Did the hunters even remember the tricks to contain the flames? The tribe had become lax because of the scarcity. They had built the huts close together again and no longer kept wivern skins full of rainwater. But then, the villages were always meant to be ephemeral—that was price of hunting wivern. Not this time, Jon mused, his thoughts racing with the effects of cojo leaves, this time the tribe had turned in on themselves.

And then it became clear it wasn’t just the wivern numbers that were diminishing. No, when was the last time a child was born? When was the last time their Eleeoka or their needy Earth Mother sluts had offered renewal? Only three boys in the village were younger than he, and they were on the cusp of manhood. Who would they mate with? This tribe was dying and the world along with it.

Jon increased his pace. He knew these trails well enough for the next several miles. After that he would have to slow down, but for now, the cojo would drive him forward, and hopefully his racing thoughts would keep his mind occupied as he ran.

When dawn came, he was at the edge of the world, or such was his first thought. Fog rolled low across the sand. He didn’t know he had made it to the ocean until his feet hit the froth of the tide.

The sun rose and burned away the fog. So he sat and let the cojo spend itself. He was cold and suddenly hopeless.

His mind wandered as he watched the endless waves. Koan used to tell tales of Bone Giants, men so large they could wade across seas. Kings, warriors, and mystics… extinct now—perhaps they were all eaten too. He imagined himself standing on a Bone Giant’s shoulders as they both fled across the ocean. Finally, the sun became strong enough to induce drowsiness, and after a full night of running he could not fight the need to rest. His body demanded it. He dug a small depression in the sand and fell into a fitful sleep.

###

He woke hungry, the sun low. His exposed skin was tender and darkened from the sun. Far out over the ocean, he saw the faint curve of the earth, and some distance out a silver-blue water wivern flung itself into the air and dived back into the ocean.

A bounty of crustaceans was stuck to the jetty. He knew most to be edible, and the seaweed too. Two crabs scuttled at the tide in the throes of fighting or mating, it was not clear. Unusually large sand fleas were washed to the strandline and then rushed back to the ocean in an endless cycle. He had a spark-stone in his bag, but there was little to burn on the beach, only some dry reeds and driftwood closer to the bank of trees. The tide washed over his feet as he collected the sea creatures and ropes of seaweed.

In a valley of dunes, out of the wind, he squatted. His balls hung through a rip in his pants, nearly touching the sand. He banged rocks together to make sparks against the damp reeds. They smoldered, and he added a bird’s nest he had scavenged, and finally he saw flame. He fed the fire slowly, bit by bit, until the flame raged. When he’d found the nest, he had found eggs dappled with violet spots, small things not much bigger than the tip of his thumb. He returned to the sea to gather water in a wivern-skin pot. The leather was stiff yet soft enough to fold; the frame was made from milled wivern bones. He put the pot directly on the flame and rimmed his tiny hearth with rocks. When the water boiled, he dropped in his motley collection of edibles… two crabs the size of his palm, a handful of barnacles, the eggs. He watched them roll in the water. Instantly there was a rich smell.

###

Jon left the fire smoldering. There was nothing but sand for miles, and what if a stray spark did catch the world afire? What was it to him? Or them? Let it burn. His meal was small (one dappled egg had been quickened, an omen of luck in his tribe), but it was enough to give him the strength to move. No more running, though. The cojo had tapped his reserves, but the toll on his body was unmistakable. His calves had cramped and he’d kept running, his lungs had filled with phlegm and he had kept running, his spine had banged between his hips, he kept running. Koan had taught him the endurance and benefits of trances. Jon scoffed at the idea of a spirit world, but he knew there was a divine spark in the human body, something that demanded preservation and respect. It demanded it now.

“Sentience?” Koan croaked in his mind.

Jon Quiddity looked out to the ocean. Billows of clouds were pasted over the orange sun. In the waves, three small water wivern broke through and caught the air. They glided along the surface without flapping their bony wings. In a sudden bout of anger, Jon turned and faced the way he had come. He thrust his crotch in insult toward the distant village and bellowed a curse of extinction upon them.

###

The next day of travel brought the mountains. He left the beach and followed the paths; he’d never been this far north before. He knew the hunters had, but they rarely spoke of their adventures. Like the mogul, they preferred to keep their doings mysterious. They preferred to keep themselves valuable. The distant mountains were tipped with snow, but here the scorched earth stunk of sulfur. There were caves in the rocky outcrops. Golden veins of minerals were embedded in the cliffs. The raw ore was as plentiful as the clouds in the sky, as plentiful as the splinters of invisible wind that cut into his cheeks.

“This is exile, Jon Quiddity,” Koan said.

He thought of what might lay beyond the mountains—Quemazon. Even the hunters had not ventured beyond the other side. Most thought there was a never-ending wasteland of burning earth and chutes of molten soil that flowed constantly, that wivern were birthed there and pushed out into the world in glowing fetal-shaped lumps of lava that became eggs when they cooled. Like the professed hoax of Koan’s spirit world, Jon did not believe this any more than he believed men were birthed from river mud.

Onward and upward he traveled, between the canyons and paths, around cliffs and chasms. Higher, until the clouds were snared on the mountaintops and slipped into the valleys. The ground fog was so thick and clammy, he could not see an arm’s length ahead. He began to feel chilled with an unreal fear he had gone somewhere a man did not belong. It was eternally dusk here… he had lost all sense of time and reason. He chewed more cojo leaves. Hungry but not weak, he felt light and free. His backpack weighed nothing, his heart carried no burdens, only the next step was on his mind, and the next, and the next.

###

On the beach, with his face painted for a hunt, Gavin picked through the ashes of Jon’s fire. He found the dappled eggshells, smashed bits of barnacles, and knots of inedible rockweed. He sifted the cooling ash between his fingers. Deep in thought, he endured the sting of the embers. Behind Gavin, the village smoldered like the ashes in his hand. When the wivern were more numerous, it was not unusual for a village to burn. They’d recover, there were no deaths, in fact, the children and women still fed wood to the pyre where the mogul’s hut once stood.

Jon had made no effort to cover his tracks; he’d gone to the mountains. Gavin followed his footprints.

The elders had spoken. He was to extract the secret of purification of wivern flesh, then kill the so-called mogul before he brought more curses on the tribe. Gavin had agreed to go, if alone, and he would kill John Quiddity—not for the secret he did not know, but the secret he did.

###

Upward and onward, Jon pressed hard. The cojo leaves were nearly gone He had enough of the juice in his blood to last for another day, perhaps longer, but there was the question of putting the raw energy into his body. While the cojo suppressed hunger, he kept an eye out for anything edible. Little presented itself. A familiar type of beetle, the size of his palm, was numerous. He collected them, but without the ground-up tubers to feed them and thus purge their bowels, they were less than appetizing—food for dogs. He was sure he’d be hungry enough before the sun set tonight, but at this moment he was content to gather them.

Onward and upward for hours, then the thunder rolled across the hills in terrible crashes, and the lightning came in jagged yellow streaks. The air stunk of something burnt. It was cold instantly, and still the fog rolled. Rain, a great torrent of it, it ran down the path, it rolled boulders and rubble. In minutes, Jon found himself fighting to not be swept away. He saw a crack in the mountain; it was elevated above the path that was now a river of mud. He made his way into the crevice—it was larger than it first appeared. He felt a moment of relief. Safe now, perhaps not entirely, cold and hungry, but at least alive with no immediate threat.

Then, as he stepped deeper into the cave, he smelled the familiar and unmistakable scent of a wivern.

The storm dimmed the cave, but he could hear the slithering of the beast. Its eyes glowed with a cold luminescence. It hissed, and the stink of ammonia filled the cave. Jon backed up, stumbled, and fell. He hit his head on a rock jutting from the wall, then clutched at the crop of rocks to keep from falling. The wivern hissed again; the fumes gagged him. He backed toward the entrance and saw that way was death as sure as what was in front of him. A mudslide had caused the path to become a raging river of sludge filled with boulders and tree trunks. He clenched his jaw so tightly he was sure his teeth would crack. Finally, in his horrified desperation, he remembered Koan’s proclamation of wivern sentience.

“Do you speak?” Jon said. His voice trembled. He allowed the fear as he allowed the chronic pain of his isolation.

“My eggs,” the wivern warbled like a choir. It slithered again in a dangerously perfect sound—the scratch of scales on scales. It exhaled when it spoke, and blue flame sprouted, revealing serpentine features and a set of vestigial legs and bony wings. Jon only got a glimpse. Instead, he was focused on the three lightly colored eggs the size of his head. The wivern blew another flame, but it was clearly only a display of aggression and not meant to hurt Jon.

“Get out, hunter. Go and you will live,” the wivern said.

“I can’t go,” Jon said. “The path is gone, and I am no hunter. I’m only a traveler, a mogul.”

The wivern screeched and blew a stream of gleaming green fire.

“No! Get out!”

Why wouldn’t she just burn him to cinders? Perhaps the flame would damage the eggs? Yes, Jon decided, that was it.

Jon said, “I don’t want to hurt you. I don’t want to be here. I’m exiled. I want to go, but I cannot.”

The wivern moved up; its neck grew impossibly long.

“Leave,” she hissed.

“Does your kind have moguls?” Jon asked. He was desperate for any engagement.

“Moguls? Done. My kind done. All done,” she said. “Hunters.”

“I’m not a hunter,” Jon said. “I am a mogul. I have no tribe.”

The wivern recoiled quickly, and by the location of her eyes, Jon could guess she had wrapped herself around her eggs. Jon had once overheard the hunters speak of wivern flame. Like the venom of an adder or the sap of a man’s root, their fire was limited to few bursts before it needed to be regenerated.

“I am not a hunter,” Jon said. “I beg shelter until the storm has passed.”

“No,” she said, but her voice was soft and accepting.

“I have no choice.”

She was silent now, for some seconds, then finally: “I will kill you if you go near my eggs.”

Jon nodded.

“I understand.”

Outside, the storm raged.

Down below, a half day behind, Gavin weathered the storm at the foot of the mountains, lashed to the trunk of a tree.

###

An uneasy truce fell between the wivern and Jon Quiddity. Jon lit a tallow candle from his pack. He saw by the scant, flickering light, the cave was tiny, barely enough room for the wivern and her eggs, much less room to attack a man and have any hope of not destroying the eggs. There was a certain beauty in the wivern. Her eyes were set at a slant and protected by a majesty of tiny horns. Her ears rose sharp as a knife blade. Her iridescent scales shifted hues of color—with the candlelight or fear, Jon did not know. The never-ceasing change of color reminded Jon of seashells. The embers that were her eyes glowed with a cold light, unlike the fire that brewed in her chest. Then there was the smell of fresh wivern urine, a distinctly inhuman scent. From the shadows, he saw her evaluating him as he evaluated her.

“I am called Jon Quiddity. I am mogul of my tribe. Exiled now,” he said. He tried to inject pride into his voice. “What is your name, wivern?”

There was silence.

“Do wivern have names?” he asked after no reply came.

“Of course,” the wivern said.

“And what is it?”

Silence again, then she spoke. “Saa-delia,” she said.

He said it back to her, but she did not respond.

“Do you have a mate?” he asked.

“Dead,” she replied. “Two moons ago. Hunters.” She slithered again and blew wisps of flame. It clearly agitated her. Jon said nothing—two moons ago was his tribe’s last kill.

“When the rain stops, I will go,” he said.

Silence. He could hear the beetles he’d collected scratching in his sack. He wondered if it would offend Saa-delia if he ate them. Hunger had made him weak and light-headed. He hoped his judgment had not failed. He put the first beetle into his mouth. It squirmed between his lips, and then it squirmed in his mouth as he crushed the life from it.

If there was offense in the act, Saa-delia said nothing.

Hours passed. Jon, too anxious to sleep, too tired to be mortally afraid, just sat. Hunger returned, and he finished the last of his beetles and dozed off.

###

Seemingly minutes later, Jon came awake in utter darkness. He was not sure where he was at first. Then when he reconstructed his memories, he was sure they were false. Saa-delia stirred and vented a gush of ammonia vapor into the cave. Not enough to knock the breath from his mouth but enough to validate the reality of the situation. If she’d spent her flame earlier, it would be replenished by now.

“Jon Quiddity, beetle-eater, mogul, nomad,” she said. “The storm is spent.”

Indeed, Jon did not hear the thunderclaps or the steady tap of rain. He squinted at the cave entrance. It was dusk or dawn; he did not know for sure. He stood. His body ached; the cojo root would help with pain. He took the last of his leaves and put them into the back of his mouth, mashed and sucked the juice down. He stood at the doorway. The rain had stopped, but the path continued to flow in a slow, muddy river. It was at least up to mid-calf; it would be impossible to traverse it. He came back to the darkness.

“Go,” Saa-delia said.

“No,” Jon said. “Not yet.”

He sat down again as the cojo puckered his stomach and soaked into his aching limbs. The cojo, as it might have with Gavin that first night, destroyed his judgment.

“I didn’t know. A lot of us don’t know. I am mogul. I didn’t know until just weeks ago,” Jon said.

“What?” Saa-delia asked. She slithered again.

“That the wivern are, no, that you are sentient.”

“What?” she said.

He considered.

“Alive,” he said. “No… that you can talk. That’s not right either. That you can think, that you know you exist. Do you remember when there were cattle?”

“Yes,” she said.

“Cattle—they are not aware. They do not know themselves—”

Saa-delia made a grunting noise, as if she had little interest in the topic. Then there was the crunching of what Jon first mistook for bone, but no—he saw by the flicker of his candle, it was the roots that grew into the cave. She drew sustenance from them.

“Sentient,” she said.

“Our hunters are… it’s not… ” Jon did not know what he was trying to say. “I’m sorry.”

She slithered again, scales on scales. “Peace,” she said.

“My tribe lost a secret when the old mogul died. They will no longer hunt wivern.”

“They will hunt us,” Saa-delia said.

“You are sentient. I will tell them.”

“You are exiled, and they know,” Saa-delia said. She slithered again. “Our secrets need no defense, nor our truths. We will kill hunters, hunters will kill us, we will burn your villages, you will smash our eggs. This is the way it will be.”

“The hunters smash your eggs?” Jon said.

She was silent.

“I can go soon.” He looked out the exit of the cave. The mud no longer flowed. It would be hard going, but in hours he could make his way along the path. He tested the mud with one foot. It was thinned to the point that, if necessary, he could leave, if he was strongly motivated. Clearly though, Saa-delia would have attacked if that was in her nature. She wanted to protect her eggs. An unexpected feeling of safety came upon him. Then tiredness, absolute and overwhelming. If he hadn’t such a scorn and skepticism for glamours, he’d think one had been put upon him. Finally, before he decided to let the drowsiness seduce him, he realized that the cojo’s juice was claiming its price, as it always did. He’d sleep now and let his body pay back the borrowed energy.

“I must sleep first, though,” he said. “I need to rest.”

She slithered again.

“Sleep, then,” she said, “dream of what might be.”

Jon Quiddity sat with his back against the wall. Outside, the sun burned the fog away from the canyons and dried a thin layer of mud where it had flowed. Under this sun—among the dirt and exposed roots, rich golden ore exposed to the elements—under this sun, Gavin picked his way through the boulders and uprooted trees.

###

Gavin stood in the doorway, a silhouette, a statue.

“Jon Quiddity,” Gavin said.

Jon was incredulous. He was unsure if it was a dream or a reality twisted by the strain of the past days, perhaps both.

“How did you find me?” Jon asked. His head thumped from the cojo’s aftereffects.

“You are a clumsy prey,” Gavin said, his tone cold and ungenial. “I can track a bull wivern under a moonless sky. My powers of observation are without equal—”

Saa-delia slithered in the shadows, rose up, and struck at Gavin like an asp.

“Hunter, I know you,” she said. “I smell the blood of my husband.”

Gavin was stunned. He stumbled back, but true to his imbecilic bravery, he drew his knives, one in each hand. He regained his composure in the few seconds it took for Saa-delia to recoil before she made another strike.

“Here there is a wivern,” Gavin said. “I will kill it.”

“No! There is a truce,” Jon said. “Please, Saa-delia!”

The sun broke through the clouds, shone in through the mouth of the cave, and lit it as bright as day. Saa-delia was livid with red and black, bewilderingly coiled into a ball, precise and almost inorganic. Her face was wise and tragically hopeless. She struck again. Gavin, practiced and sleek, dodged.

“She’s brooding!” Jon said.

“All the more reason,” Gavin said.

Saa-delia rose up again. Seemingly without premeditation, Gavin sheathed one of his knives and used his free hand to pull Jon in front of him, making a shield of Jon’s body. Saa-delia’s sharp face bore down on them both, and then… all was black.

###

In the darkness of a small death, Jon dreamed of peace, of an imagined mother shedding her skin, of a beautiful man with the head of a wivern, that he had wings that sprouted from his spine that grew a season of vicissitude in an instant, then withered…

###

Jon Quiddity opened his eyes. The smell came: burnt flesh, blood, and ammonia as wretched as anything he’d ever known.

He leaned on his arms and turned to see Gavin torn limb from limb. His flesh was charred to black. His intestines hung, unraveled and stinking of shit. There was nothing left of him that resembled a man, nothing left that was not torn fragments. Saa-delia lay, her face and neck cut. One orb was deeply gashed and swollen, the light gone. She would not live. Two of her three eggs were crushed, the embryo recognizable but in a primitive state. The third egg seemed to be whole, splashed with blood and muck, but whole.

She must have found some indignity in licking her wounds because she stopped when she saw Jon was awake.

“Hunters,” she whispered. Blue flame came up from her nostrils as she exhaled the word.

“No, no,” Jon Quiddity said. “This… ” He breathed deeply as he tried to find a calming thought and then gagged on the eye-watering stink.

“My eggs,” she said.

“One is whole,” he said. The blue flames that came from her nose became smaller, then disappeared all together.

“I am not whole,” she said and was finished. Her head fell flat, her bowels failed, and a stream of brackish fluid ran from her body. It smelled of pine pitch and feces.

The stench and the horror of the cave finally became too much for him. Jon stood and turned, but unable to avoid one final look, he turned again… the egg. Yes, the egg was perfect, perfect and whole. He could carry it, if he was careful. Certainly he could nurture it, then deliver it into the world, but to what end? What horrors had this dying place offered him? He’d been midwifed from the corpse of a woman too. Despite being raised by a tribe, he might have been a wivern among them. To not know the horrors of this world! He owed Saa-delia nothing, certainly less than he’d owed Gavin and his tribe. Better to finish what Gavin had started, then let what was inside the egg wither and die. Better to set it free.

A breeze stirred and brought the fresh mountain air to the cave. He found a rock the size of his fist. He stood over the egg and let the air cleanse his lungs.

His fist rose up.

“Dream of what might be.” Saa-delia’s voice came as Koan’s had—a ghost, nothing more. Jon wept but did not sob. His fist went down and hung at his hip. He dropped the rock. He would take the egg over the mountains to Quemazon. There the earth still birthed wivern. He smiled, resolved but not convinced. A single egg was not fair compensation—his tribe had killed hundreds of wivern—but then he thought. He was not his tribe, his tribe was not him, and perhaps this world was better without tribes anyway.

An incredible story. Brilliant. I couldn’t turn away.