By Nick Thiwerspoon

[Aan David en Annetjie, met wie ek dikwels hierdie berge geklim het. Waarookal julle is, mag die Dame jul in Haar hand veilig hou en julle vrede gee. Ek mis jul, liewe vriende.]

Ja[1], I know. I shouldn’t have gone climbing by myself. But my man had walked out on me – with a Western Province rugby player, nog[2]. I thought rugby players were supposed to be so macho and straight. Not this one, obviously. Anyway, I needed the peace and solitude of the mountains to recharge my batteries. And since that naaier[3] Johann had left me, I had no-one to climb with. OK, maybe the truth is that I was in a self-destructive mood.

The weather forecast wasn’t too bad: “Clearing showers”. I should have remembered that they always got the forecast wrong. There was a strong south-west wind, which felt as if was coming straight off the Antarctic, when I drove up Du Toitskloof Pass, and the peaks of the Klein Drakenstein mountains were thickly swathed in cloud, but I was determined to have my time in the open air. Amazing how stupid you can be when you’re grieving.

I began to feel better as soon as I reached the first Mountain Club hut, in the pass itself. It was built a long time ago, long before the old national road was constructed in ’48, never mind the new freeway. Made of rough brick and timber, and surrounded by a country garden of plants which could look after themselves, it had always been a place of peace for me. It didn’t matter that I had brought Johann there. I felt tears come to my eyes once or twice, but I was all right. Yes, I know you don’t believe me, but it’s the truth, I promise you.

There was no-one there. Of course not – they were all at home in front of roaring fires. No-one was so stupid as to be out in the mountains in such bad weather. Except me. I made a small fire from the logs stacked outside. I didn’t bother to go searching for new wood to replenish it, like you were supposed to. Johann and I had scoured the nearby slopes to find fuel last time we’d come, so I felt I’d done my share. I didn’t feel in the mood for it, anyway.

I cooked a small tinned stew on the fire, and washed it down with some brandy and coke. That was one of Johann’s complaints about me. I wasn’t sophisticated enough. Maar fok my[4] – just how sophisticated is a WP rugby-player, wou ek net vra[5]? More like he was hot in bed, he had a nice arse and a big cock. Johann didn’t much care about sophistication when sex was involved. In fact he had quite unsophisticated tastes, there: big, meaty, manly. Everything I wasn’t.

The next morning the temperature had dropped sharply. The wind had swung from south-west to due south. I should have given up there and then. I could have gone to a gay club that night. Instead… but we’ll get there.

There was no way I was going to have a bath in the swimming pool fed by the water of the crystal-clear and absolutely freezing mountain stream that fell in a torrent down the side of the Sneeuberg[6] and ran behind the hut. What did it matter if I was smelly?

The path from the hut rose over the nek[7] and then followed the river valley to the next ridge, about five or six kilometers away. As I plodded up the slope, it began to rain hard. It was freezing, but I was warm underneath the layers. Look, I’m not completely stupid. I’ve been climbing for a long time. I knew these mountains pretty well. I had spare food in my rucksack, long underwear, a Gore-Tex jacket, a polar-fleece jumper and a stout hiking staff.

I climbed the next ridge up the zigzag path that ascended its steep face. As usual, it seemed to last forever. At the top, there was a little mist. I was almost in the cloud line. “Clearing showers”. No need to worry. This bad weather was all going to go away soon. And since this was the Western Cape, the cold front would be followed by sunshine and stillness. The mountains would be absolutely perfect in that sort of weather – purple and blue and grey, the very shadows of the kloofs and native forest tinted cobalt and sapphire by some magic of the mountain air.

I went on.

About a kilometer across the high plateau that extended behind the ridge to the next range of mountains, it began. All at once, so quickly I had no time to turn around, the cloud-line dropped. The mist above my head was suddenly right on the ground, so thick I could barely make out the path in front of me. I wasn’t far from the next hut. And I knew the way there. Of course I did. I went forward.

You know what happened next, don’t you? Natuurlik[8]. I got lost.

It gets better. What the weather bureau hadn’t thought to mention was that above a thousand meters, these “clearing showers” were falling as snow. And they weren’t clearing. The southerly, which cut into my face sharp as a knife, settled down to blow even more strongly and steadily. The snow soon changed all the familiar landmarks. I kept walking to keep warm. But I knew it was pointless. By morning I would be dead. I wondered if Johann would be sorry, if he’d even care or notice. Probably not, I thought bitterly. It was eerie in the cold silent white, the snow and the clouds muffling all sounds, dulling even the whiffle of the wind. I felt an almost supernatural terror, a sense that I was close to the otherworld, that it would all soon be over.

My feet and my hands were freezing cold, soos ’n heks se poes[9], but my body was warm. I started to feel sleepy. I knew this was a sign that I was getting hypothermia, but I was beyond caring.

Then I heard the whistling. At first it was Sarie Marais[10], that old favorite of the Afrikaners[11]. Whoever it was whistled well, joyously, in tune.

”Hello!” I shouted. “Who’s there?” I repeated it in Afrikaans. After all, South Africa is a bilingual country. Actually, a multilingual country, but in those days, only the languages of the White settlers counted. But in any case I thought it unlikely that the whistler was Xhosa. Not with that song, a love song from the Boer War. The whistling continued. I wondered whether my ears were deceiving me. The mist was so thick, and the falling snow blanketed sound. I was sure this was the beginning of oxygen starvation or blood sugar deficiency or something similar.

Then the whistle changed.

Hello my baby

Hello my honey

Hello my goodtime gal

Send me a kiss by wire

Baby, my heart’s on fire

If you refuse me

Honey, you’ll lose me

Then you’ll be left alone.

Nice syncopation, first-rate swing to it. Male, at a guess. And he liked jazz. Suddenly I wanted to live, very much. Johann se poes![12]. Heartless bastard! I will survive! I felt like breaking into song myself.

“Hey!” Once again I was ignored. Of course, sound travels strangely in the mountains, in snow. And the wind was southerly. He was south of me (I guessed). I could hear him but he couldn’t hear me. Obvious, when you think about it.

I headed towards where I thought the whistling was coming from. This was completely illogical, given that I’d just told myself that you couldn’t actually make out the real direction of the sound. Nevertheless, I walked resolutely towards it. It seemed to get louder. I knew I had to be careful: there were cliffs all round — it would be easy to miss seeing them in this blank whiteness. If I fell I would die of exposure by morning. And anyway, no-one knew I was here even if I did survive till the next day. Yes, I know. You don’t need to say it. I promised myself that if I survived, I would never climb alone again.

I was hurrying towards the sound of the whistler as fast as I could while still keeping an eye out for the precipices and testing the ground with my staff at every step. It wasn’t dark, just an eerie, swirling white, so I could move faster than you might think. Suddenly the whistling was very close, and then I saw him. He was ahead of me, walking along a path that appeared out of nowhere, passing between the lichen-clad boulders and the giant protea shrubs. He was about twenty yards away, wearing a blue and white striped rugby guernsey, the colors of U.C.T.[13] and Western Province, and of all things, drill rugby shorts. It was bitterly cold, yet he seemed quite unfazed. His whistle changed again, to another jazz number, just as upbeat as the previous one, but unknown to me. I called out to him, but again he ignored me. We continued like this for another ten or fifteen minutes, and I was just beginning to wonder whether in fact I was dreaming or comatose when I saw a dark, square shape loom out of the whiteness.

It was a small timber cottage. I hadn’t known there was one around here. As far as I knew there was only the Mountain Club hut, on the slope above the steep gorge of the river, and beyond that, for several kilometers in all directions, no farmhouse or workers’ cottage. That was after all the attraction. If you were lucky, and there were no strangers sharing the hut with you, you enjoyed complete privacy. That had been good when Johann and I had come up here. There’s something magical about making love in front of an open fireplace, soaking up the warmth, lying there afterwards, warm and sated.

The man opened the door, and turned to look at me. I was close enough to make out his face. He was smiling. His eyes were grass-green, his hair sandy, streaked to blond by the sun. I could see the warm yellow light of paraffin[14] lamps inside, and, in a stone fireplace, a fierce blaze. It looked so welcoming and safe. He beckoned with his head, and I started to walk towards the door. I was utterly confounded when he abruptly closed the door in my face. But I wasn’t going to freeze to death outside when there was warmth inside, no matter the occupant’s manners. I pounded on the door. “Hello! Anybody home?”

The door was opened after a few agonizing minutes by another man, not the man who had just gone in. He had thickly curled brown hair, and warm brown eyes. He was strongly built, with muscular arms and legs, and filled his Aran sweater and trackpants well.

“Kom binne[15],” he said.

“Dankie[16].” I went in. The warmth was blissful.

“Sorry to bother you like this,” I said in Afrikaans, “but I got lost.”

He heard my slight English accent, and switched to English. “Not a good day to do that, nè?”

“No.”

He looked me up and down. “You need something warm in you,” he said. He took a percolator pot of coffee from the hob, and poured me a mug, putting a generous splash of brandy into it.

I took off my rucksack and leaned it against the wall next to the door. I looked around me. There was just the one room. I supposed that, as was the case with the Mountain Club huts, the toilet was outside – a longdrop fifty yards from the cottage. There was no sign of the other man, the whistler.

“Where’s… ” I paused for a moment, not wanting to appear stupid.

He met my eyes, and waited. They were steady, but, disconcertingly, filled with a mixture of wariness and sorrow.

“…the other man?”

He dropped his eyes, and busied himself with pouring some coffee. “There is no one.” His voice was gruff, his accent stronger.

“But… ” I stammered.

“Niemand nie[17]!” His tone was uncompromising.

I nodded. I was in no position to argue. I had seen someone go in, and he wasn’t here now, so there had to be some logical explanation.

“What happened?” he asked, in Afrikaans.

“Dumb as donkie drol[18], that’s me.” I was deliberately light. I didn’t want to discuss my disastrous personal life with a stranger. Especially a straight stranger. “The ou[19] I was going to climb with couldn’t make it, so I came by myself.” I shook my head regretfully, hoping I’d avoid a well-deserved lecture.

He smiled suddenly. “Lucky you found the cottage.” His tone was dry.

“Yes,” I said, reluctant to mention the other man again, the one whose existence this man so vehemently denied, and who had saved my life. “Ek heet[20] Sam.” I extended my hand to shake his.

“Pierre,” he said, holding my hand in his meaty paw for a moment. He gave it the Afrikaans pronunciation: ‘Pierrie’. “You’d better stay the night. It’ll be dark soon.”

My eyes drifted involuntarily to the bed. The only bed. I supposed I could sleep on the floor in my sleeping bag. I’d done it often before. I certainly wasn’t going to complain. I was, against all expectations, alive. What did hard floorboards matter in that context?

“It’s a big bed,” Pierre said, his eyes glinting with amusement.

That was fine by me. I was the gay one here. I would keep on my thermal undies, and sleep facing away from him. I wondered why I felt desire for him. He wasn’t conventionally handsome. I would not have looked twice if I’d met him in the street. But there was an intriguing mixture of sorrow and vulnerability and toughness in his face. And his body, though not an athlete’s, was pretty good – no boep[21], broad shoulders and thick thighs, and a nice package. But my gaydar detected nothing. Compared to this man, compared to anybody, Johann was beautiful – there is no other word – and he was in addition my first love. Losing him had made me sick with grief. I was ready to be comforted, even by a stranger, even a plain one. So it was with regret that I decided Pierre was straight.

“Are you hungry?” he asked, in Afrikaans. “It’s a good way to get warm, fill yourself up with food.”

“I am a little,” I admitted. “I have some food in my rucksack.” This was a subtle reminder that I might have gotten caught out in a storm, but I was prepared, not some hopeless tyro.

He went over to the cupboard in the corner, and took out a tin. He also had fresh fruit and vegetables.

“Did you bring all that up with you in your backpack?” I was astonished.

“No.” He was amused. “I drove up. There’s a forestry track up from the Worcester-Grabouw road. It’s a fair hike from where the track ends, but not impossible. You can see the end of the road from the stoep[22]. It’s about a K or so away, down the slope.”

I took his word for it. I was still too cold to willingly go outside. I shivered.

“I hope you haven’t caught a chill,” he said, his forehead creased with concern.

“Me, too.”

It was nice of him to care. “So, why were you climbing by yourself?” His gaze was unjudgemental.

“I felt I had to climb. I needed the mountains. It was all planned, but at the last minute, my . . . . friend couldn’t make it.” ‘Friend’. Johann hadn’t even bothered with that old lie ‘it isn’t you, it’s me’. His eyes had glittered with spite as he’d dumped me. Despite my resolution, my voice caught.

Pierre’s eyes met mine for a moment.

I didn’t want to talk about Johann’s perfidy with a stranger, especially a straight stranger. I heard whistling from outside the hut. “What’s that?” I asked sharply.

“What?”

“I hear someone whistling. A jazz tune.”

Pierre looked at me and I could see into the depths of his heart. His soft brown eyes were filled with pain. My own heart twisted, as if someone had placed a hand on it and squeezed. “I heard nothing,” he said. He looked away. “Speel jy skaak?[23]” he asked, his gaze fixed on the scarlet and buttercup-yellow flames in the fireplace.

“Ja.” Good manners demanded no less, though I couldn’t, not really.

He produced a miniature chess set, and poured us both a glass of brandy and coke. We played several games. He trounced me every one. By this time we were both slightly drunk.

“You’re a terrible player,” he said leaning back in the chair, his smile teasing.

“Dankie, meneer[24]!” I had to force myself to stop looking into his eyes. He was straight. And I was on the rebound.

“So what are you good at?” He’d switched back to English.

Love, I thought. I’m good at loving. Aloud, I said, “W-e-e-l-l, I’m a programmer. I’m good at that.”

“You should be good at chess then!”

“But if I make a mistake in a program, I can go back and redo it, fix it. But in chess, I can’t.” Like life itself, I thought bitterly. “What are you good at?”

“Ag, ek weet nie[25]. I’m an architect. Am I good at it? Who knows? We were taught to build stuff in the modern way, but I prefer the old designs, the simple elegance of Cape Dutch. Especially when it comes to the buildings of the poor. The Malays[26] took the designs of the Dutch and simplified them. But they retained the three great principles – symmetry, proportionality, simplicity. And they produced some of the most beautiful buildings in the world, almost instinctively.”

I could see this was close to his heart. His eyes shone, his face was mobile and excited.

“But other architects look down on me, I think. They ape overseas fashions – Mies van der Rohe, Bauhaus, le Corbusier.”

“You think you do a good job?”

“Ja.”

I smiled at him. “And are you vain or in love with yourself?”

“Nee[27]!” He pretended to be indignant.

“Well, then, you probably are a good architect.” Dammit, I was coming to thoroughly like him. And I suddenly realised that since I had arrived at the cottage, I hadn’t thought very much about Johann.

It was still snowing heavily. The only sounds were the strong southerly, shrilling around the hut, and the crackle of the fire. July, mid-winter, and the sun was setting early. The yellow light from the paraffin lamps reflected from the windows and the mysterious whiteness outside. I heard, almost at the edge of perception, someone whistling Sarie Marais, and I glanced at Pierre, but his gaze was fixed on the fire.

We drank some more. He got up. “Just going to piss,” he said.

“I need to, too,” I replied.

We went outside and wee’d off the stoep, facing away from the wind, companionably, two men together. The air was piercingly cold. Even in those few moments, my ears started to ache. Pierre grabbed some logs from the pile underneath the stoep and carried them inside. I grabbed some too, and added them to the stack next to the stove. He piled wood into the stove and opened the vents a bit wider.

He poured us each a glass of brandy. We talked for hours, about architecture, politics (as one always did, then, in South Africa), about our jobs, about family and the rugby this season, books we’d read, everything except love and sex.

Eventually, the brandy bottle was empty.

Pierre tipped the bottle upside down, said, “Hy’s dood[28],” and started to undress.

He was wearing old-fashioned white briefs. Somehow this was endearing and surprisingly erotic. I could imagine Johann’s reaction, his spiteful scorn and his sarcastic asides. But Johann was in someone else’s bed, and wasn’t anything to do with me any more. And Johann was a selfish bastard. I was well rid of him. Why, then, did it still hurt so much?

We both lay in the bed on our backs, staring at the unadorned fibre-cement sheets of the roof.

“Did you build the hut yourself?” I asked.

“Me and Stephen. It took us months. We had to bring everything up from the end of the road. I hired some workmen to help move the heaviest stuff, and a builder I often use helped me. It was hard.”

“Who’s Stephen?”

There was a long pause. “Hy was my man[29].”

I was so taken aback I was silent long after politeness required a response.

“Ja. Ek is ‘n moffie[30].” His voice was startlingly bitter.

“Ek ook[31].” I spoke quickly. I didn’t want him to feel like that. I turned to look at him. “He was the ou[32] who brought me here, right?” I asked.

“Yes.” He lay on his side, looking at me. His eyes were filled with sorrow. After a moment, he said, “He was a soutpiel[33].” He smiled a little at this ancient ritual insult.

I waited, resting my head on my elbow as I examined his face. I couldn’t believe I had gotten it so wrong. My gaydar was never wrong. He seemed completely straight.

“We met at a rugby game. I was playing for the Maties, he for the Ikeys[34].”

I remembered the man who’d led me here had been wearing a U.C.T. guernsey. I listened for any ghostly whistle, but there was no music — perhaps the distant cough of a leopard, the calls of a troop of baboons, but mostly the muted moaning of the wind.

“What happened?”

Pierre thought I was asking about how they met. “The two teams went for beer after the game. He tried to talk Afrikaans to me. At first I was annoyed, because his accent was so bad. How can someone live in this country and not learn the other official language? But then I realised, from something he said, that he was English. I mean from England. He’d only been in South Africa a year or two.”

I watched him, admiring the warm chocolate of his eyes.

Pierre continued. “So it showed he wasn’t arrogant. Anyway, we had a few beers. He asked me to teach him Afrikaans. It was just an excuse, I think.” His smile was nostalgic, melancholy. “He never really learnt to speak it properly. Well except for the bed words. And you?”

I raised an eyebrow.

“You said earlier about your climbing alone. You seemed really sad. I assumed…. ”

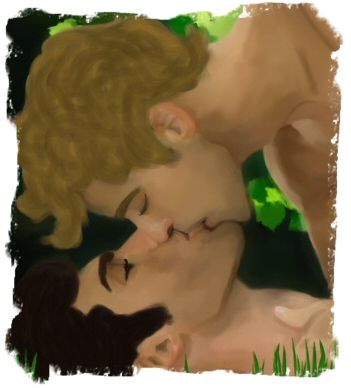

So I told him all about Johann. And when I began to cry, trying not to let him see, he took me into his arms and kissed me. He tasted good. It felt right to be in his arms. And after, I found out that his cock was as meaty and as big as his hands, and that it was wonderful in me, and that he was a roarer when he came. It was unexpectedly satisfying. But even better was the knowledge that he really cared, that unlike my naaier[35] of an ex, he cared about me, about my feelings. Sometimes ‘in love’ is inferior to simple kindliness and affection. Especially if you have good sex, too. We slept cuddled against each other, warm under the thick duvet, and when we woke, the sky was a clear baby blue, and the world was azure and white, and the shadowy kloofs gleamed purple and navy threaded through with gold. Already, waterfalls of snowmelt were beginning to pour off every cliff face.

He hugged me. “Môre, skat[36]!” I pulled him into my arms and kissed him, and we made love again. Impaled on his cock, I looked down into his eyes, and then leaned forward to push my tongue against his, feeling a profound need to connect with him this way, to merge my body with his. I never thought of Johann at all.

We had a late breakfast and spent a lot of time cuddling, and then, bundled up against the cold, we sat on the stoep and talked, about life and us and Stephen, our breath smoky in the champagne air.

“What happened to him?” I asked.

“He was killed in a motor-bike crash.” Pierre swung his legs over the edge of the stoep, which had no railings. “He loved his bike. It’s strange, you know, he was so normal, so manly. You would never have guessed he was a moffie. He was just a rugger-bugger, who liked living hard, and who loved me.”

I looked at him. “Jammer, ou maat[37]. It can’t be easy.”

His eyes filled with tears. “No. Never. But I did have him, for a while. He made me happy. You know how hard it is to find someone, if you’re like us. And I found him. Maybe you are only supposed to have a little happiness in your life. Maybe there’s only so much to go around, and it has to be spread thin.”

I reached out and took his giant mitt in my smaller hands. I couldn’t bring myself to say anything past the lump in my throat. I just held on to him and we contemplated the snow-covered ranges marching into the distance. I could never have done that with Johann. He could never sit still. He never liked quietness. I suppose it made him think about himself.

Later that day, we hiked down to Pierre’s car, a Mercedes-Benz. He might not have been a conventional architect, but he clearly made plenty of money. The dirt road from his hut led through to Worcester so we came through the pass to the Du Toitskloof hut from the east. At the trailhead, he got out of his car and watched me as I stowed my rucksack on the back seat of my Mini.

On impulse, I hugged him. “Thank you for saving my life,” I said, my voice suddenly choked. Thank you for being so kind, I wanted to add. Only I couldn’t bring myself to say that aloud.

“Thank Stephen!” he said. “He led you to the cottage.”

“Thank you, Stephen,” I said obediently, grinning, then felt a frisson of superstitious terror as I listened for a whistle, which never came.

“Would you like to… ?”

“How about… ?” We spoke simultaneously. And smiled at the same time, too.

“Dinner?” he said, raising his eyebrows.

“My place or yours?”

“I asked first, so mine.”

So on Wednesday evening I found myself preparing to drive to Clifton, a suburb on the Atlantic coast. Just before I left my flat, I got a phone call from Johann.

“How are you?” he asked, his voice warm and vibrant with sincerity, full of the casual charm he did so well.

“I’m wonderful!” I felt an unexpected surge of spite. “I feel marvellous.”

There was a nonplussed silence at the other end of the line. Then, “Would you like to go out for dinner?” He very much wanted to ask me something else. I knew him too well not to guess what.

“I can’t,” I said with immense satisfaction. “I am going out for dinner with someone else. In fact, I was just about to leave.”

“Cancel it,” he ordered.

Before, I was so in thrall to him I would have unthinkingly obeyed. “No,” I said. I was quite calm about it. Whether or not Pierre and I ended up together, I knew with every particle of my being that Johann was bad for me, no matter how much my cock wanted him. Pierre was kind and strong and gentle. And when he smiled he was almost handsome. And he was nice. “Goodbye, Johann.” I put the phone down with a sense of finality, and left the flat before he could drive over to exercise his charm in person. I wasn’t sure my resolve would be so strong if he was there in front of me, his grin as winning and salacious as ever, his lovely body and beautiful face weapons to be used to get his own way.

I was surprised to see that despite Pierre’s love of Cape Dutch and Cape Georgian architecture, he had an ultramodern multilevel house with concrete decks that projected out over the cliff. From them you could look down and see the breakers purling onto the sandy fringe of the cove below. We watched the sun set, out over the Atlantic, sipping a faultless Roodeberg red. Then he produced a perfect meal, a brinjal and onion lasagne, rich and savory, followed by home-made ice cream. After we’d each had a glass of imported French Sauternes, stretched out on modern but surprisingly comfy sofas next to an open fireplace, he took my head in his hands and kissed me. We made love again, on the rug in front of the fire. It felt as if I had come home.

I moved in a few months later.

Stephen didn’t reappear again. Except once.

It was almost precisely a year after I’d almost died in the mountains. Pierre and I had had our first quarrel. I stormed out of the house and went to a bar. I wanted to hurt him. And I was also missing the excitement of the chase, the pleasure of an anonymous fuck. Don’t get me wrong, I still loved Pierre. But… That old curse of gay life. There’s no excuse.

Anyway, I was sitting at the bar counter, when someone came up to talk to me. When they used to say in stories ‘my blood ran cold’, I didn’t know what they meant. But I understood then. I understand now.

It was Stephen.

He was whistling Sarie Marais, very softly, and his eyes were cold. God, they were cold. I had time to reflect that it said something about him, a rooinek[38], that he’d bothered to learn this particular song. He stopped whistling, and looked at me for a few moments. He was as real as I am, yet I felt an intense reluctance to reach out and touch him. His beautiful, cold green eyes were locked on mine. As clearly as if he had spoken, I heard don’t ever hurt him.

“No,” I said, aloud. “I won’t.” And I got up and went home.

We are still together, thirty years later. We live in South Island New Zealand now, on a wine estate in Marlborough. Pierre has designed the estate buildings in the way he wanted to. With the mountains, the vineyards, the rows of pines and cedars, and the Cape Dutch architecture, we could easily be back in the Western Cape. We go mountaineering in the area, and across the strait, near Wellington. We can’t climb like we used to – our knees won’t stand it – but we go for long hikes in the mountains, with a group of local hikers. They call it ‘rambling’ here.

I’m glad Stephen stopped me from picking up anybody. He saved me twice, actually, because a year or two after the incident at the bar, the AIDS crisis started. Yet every time I think about him and how he appeared to me that night, I still get a frisson of terror. I’ve had thirty years more than I should have. I should be grateful. And I am. Yet I wonder, when we’ve both passed through to that “undiscovered country from whose bourn no traveller returns”, whether I will have to share my dear ‘Pierrie’ with Stephen the soutpiel rooinek. I’ll be happy to share. I know how much they loved each other. And it’s thanks to Stephen that Pierre and I have had so many happy years together. The happiness was spread quite thickly, as it happens. Because of Stephen.

All the same, to this day, I can’t hear Sarie Marais without feeling a sharp jab of remembered dread and horror.

[1] Yes, pronounced ‘yah’. ‘J’, as in most Germanic languages, is pronounced like English ‘y’

[2] Yet, already. The ‘g’ is pronounced like ‘ch’ in ‘loch’

[3] Fucker

[4] But fuck me

[5] I would just (like to) ask

[6] Snow Mountain

[7] Col – which means the same thing (neck), only it’s French

[8] Naturally, of course

[9] As a witch’s cunt

[10] O bring my terug na die ou Transvaal

Daar waar my Sarie woon…

[12] Johann’s ‘pussy’. BTW, you pronounce it ‘Yo-HUNN’ and it’s the equivalent of ‘John’. You may entertain yourselves with the pronunciation of ‘poes’

[13] University of Cape Town.

[14] Kerosene if you live in North America

[15] Come inside

[16] Thank you. Pronounced ‘DUNkee’

[17] No one

[18] Donkey shit

[19] Bloke, man, guy. Pronounced ‘oh’.

[20] My name is (I’m called) Sam

[21] Pot belly

[22] Veranda

[23] Do you play chess?

[24] Thank you, sir (mister)

[25] Oh, I don’t know

[26] Brought over as slaves from Batavia (Indonesia), they became skilled artisans passing on their knowledge from father to son, mother to daughter. They are Moslem, and Malay has contributed many words to Afrikaans (piesang = banana, baie = much, many). The first book in Afrikaans was written in Arabic script by missionaries trying to convert the Malays to Christianity. Afrikaans is as much their language as it is of the descendants of the Dutch settlers.

[27] No!

[28] He’s dead (empty)

[29] He was my man. Pronounced ‘hay vuss may mun’.

[30] Yes. I’m a homo.

[31] Me too

[32] Guy. Pronounced ‘oh’

[33] Salt cock. From the old Afrikaner comment that South African Englishmen had one foot in England and the other in South Africa, so that their cock was in the sea.

[34] Maties = Stellenbosch (Afrikaans-medium) University students, Ikeys = U.C.T. (English-medium) students, so called because at one time a large percentage were Jewish.

[35] Fucker

[36] Morning, darling (‘treasure’).

[37] Sorry, old mate/friend

[38] Redneck, but not in the American or Australian sense. Afrikaners, sensibly, wore hats in the sun. The British didn’t.

© Nikolaos Thiwerspoon